|

THE

NUDE REVEALED

A

'graphic' display A

'graphic' display

The

unclothed human body has inspired many of the greatest

works of art. Central to modern western art since the

Renaissance, the nude is an idiom at once emotive and

aesthetic but at the same time equally expressive of

a wide range of ideas. Images of nudes can be beautiful,

powerful, pathetic, erotic, amusing; and relate to

us all. They contribute to an ongoing dialogue on the

most desirous or expressive relative proportions of

human anatomy; beauty very much in the eye of the beholder.

However, up to the later 19th & early 20th centuries

the classical canon largely held sway.

The

Renaissance rediscovery of classical learning, and

particularly of a literary tradition that put emphasis

on Man, introduced a whole new subject matter to complement

the biblical themes that had dominated in medieval

art. The stories of gods and goddesses whose behaviour

mirrored that of mortals, and tales of heroes who interacted

with the gods, offered an intellectual raison d’être

for eroticism. The examples of antique ideal form and

systems of proportion were an inspiration to depicting

the nude with a glorious plasticity. Venus, in representing

the ideal of female beauty, has lent her name to many

images of the female nude, as has Diana. The types of

Apollo, the ideal of male beauty or Hercules, with his

physical strength expressed through muscular beauty inspired

many images of the male nude. Knowledge of classical

mythology and philosophy were assumed in an educated

audience and old master paintings and prints are full

of narrative details and allegorical allusions both

in their form and content. The nude has also conventionally

served as a direct symbol to express abstract concepts

of truth, virtue, hope, fame, youth, the transitoriness

of life, etc.

Renaissance

thinkers sort to find correspondences between the philosophy

of classical antiquity and the Christian tradition.

This was mirrored in artistic production. Saints such

as Christopher and martyrs such as St Sebastian were

portrayed nude in a Christian equivalent to the classical

hero. Adam and Eve had biblical justification to be

portrayed nude. Eve juxtaposed Venus as an umbrella

title rendering acceptable the depiction, or even the

enjoyment of the representation, of the female nude.

The Old Testament, rather than the New, provided opportunities

for the use of nude models, particularly the Apocryophal

books which relate the stories of Susannah & the

Elders, and David & Bathsheba. These examples of

lecherous voyeurism, with their classical equivalents

in the goddess of the hunt Diana and her nyumphs being

ogled while bathing by satyrs, lent themselves as subjects

for pictures where the viewer is similarly the voyeur.

Printmaking

was developing as an art form just as the major discoveries

of antique sculpture were being made. The ancient Greek

Apollo 'Belvedere' was excavated in Rome about 1479

and would be hugely influential on future generations

of artists, including Dürer who would

have known it second-hand through drawings and prints.

Adam in Dürer’s master print of "Adam & Eve"

is ultimately based on the Apollo 'Belvedere'. Surviving

to a much greater extent than examples of painting, items

of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, frequently embellished

with nudes or only minimally draped figures, supplied

the models for artists of the Italian Renaissance. Whether

classical or biblical in inspiration the formal language

of the nude came to be based on the canons of antique

sculpture.

With

the establishment of art academies from the 16th century

on, the study of the nude formed the basis of the curriculum.

The student began by copying casts of classical sculptures

and progressed to the life-class (and beyond to the ‘dead’ class

to gain an understanding of the underlying skeletal

frame and muscular structure of human anatomy). In

History Painting, the acme of the hierarchy of artistic

genre, the composition was worked out in preparatory

studies with the figues nude, even if subsequently

clothed in the finished picture.

Even

in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century,

with Academicism outmoded, overtaken by 'art

for art’s sake', the life-class remained

central to art school education; though in general female

models began to outnumber their male counterparts. In

the popular imagination artists’ models developed

notoriety; the model in the studio became a popular subject.

The classical conventions of bathing nymphs and goddesses

transmuted into straightforward bathers in their natural

environment. However, artists have continued to revisit

the classical and biblical themes initiated by the Renaissance.

Picasso peopled his lithographs with satyrs; Chagall

illustrated the Old Testament in etching and colour lithography;

Eric Gill gave a visual reality through wood engraving

to "The Song of Songs", a biblical erotic theme not commonly

broached by earlier artists. Even

in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century,

with Academicism outmoded, overtaken by 'art

for art’s sake', the life-class remained

central to art school education; though in general female

models began to outnumber their male counterparts. In

the popular imagination artists’ models developed

notoriety; the model in the studio became a popular subject.

The classical conventions of bathing nymphs and goddesses

transmuted into straightforward bathers in their natural

environment. However, artists have continued to revisit

the classical and biblical themes initiated by the Renaissance.

Picasso peopled his lithographs with satyrs; Chagall

illustrated the Old Testament in etching and colour lithography;

Eric Gill gave a visual reality through wood engraving

to "The Song of Songs", a biblical erotic theme not commonly

broached by earlier artists.

Even in the modern stylistic divergence from the academic,

under the influences of African and primitive art which

have altered our conceptions of beauty and proportion,

and in the move towards abstraction, the nude has held

its place as a recurring genre. Hans Bellmer, the surrealist

opined

[the body] is like a sentence which incites us to

disarticulate it, so that through an endless series of

anagrams, its true contents may be combined.

Distortion and abstraction of the human nude figure have

been exploited by artists both for formal and expressive

ends.

In

modern art the nude has remained a principal theme.

It dominates the work of the greatest figures of the

French school, Matisse, Picasso, Chagall; all major

printmakers. It was important to the German Expressionists

group Die Brücke, for whom equally printmaking

itself was an important aspect of their work. It has

informed some of the best of modern British etching,

from Sickert to Lucien Freud, and inspired one of the

icons of Modern British etching, Brockhurst’s

"Adolescence".

The practice of engraving, in directly cutting into

either a sheet of copper or especially into a block of

wood, has a technical correlation with sculpture. Sculptors

have always been particularly concerned with modelling

the nude human figure and when they are printmakers too,

the nude is equally their subject. Though printmaking

was the only artistic medium which Michelangelo did not

practice, his drawings inspired many Renaissance engravers.

In the modern era sculptors have taken to engraving in

significant numbers. Represented in this catalogue are

prints by the sculptors Rodin, Coubine, Hettner, Lehmbruck,

Vieillard, Zadkine, Arnold Auerbach, and Eric Gill and

by sometime sculptors Klinger, Degas, Tissot, Picasso

and Robert Gibbings.

Just

as the human body, though consistent in its constituent

features and overall proportion of its parts, shows great

diversity between individuals, an equally rich variety

of prints graphically reveals the nude over the last

five hundred years. I hope you will enjoy the small selection

offered here in all its different aspects.

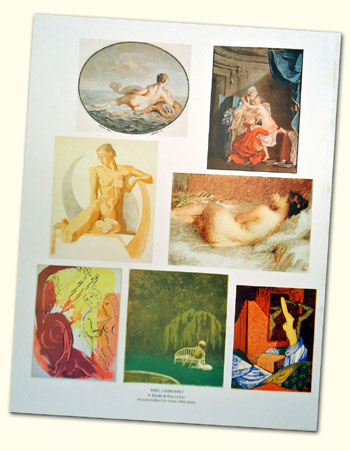

Published

2005

80 pages, 180 items described and illustrated in black and white, with seven

in colour on the back cover.

(UK

Price: £10, International orders: £15)

^ Return to the top of this page ^

|

|

Artists

included in the catalogue:

- Aldegrever

H

- Amato

F

- Audenard

R van

- Auerbach

A

- Austin

R

- Bartolozzi

F

- Baudouin

P A

- Béatrizet

N

- Beham

B

- Beham

S

- Belleroche

A

- Binck

J

- Bonasone

G

- Bouverie

Hoyton E

- Bracquemond

F

- Brockhurst

G L

- Buckland-Wright

J

- Cantarini

S

- Carlone

C

- Carracci

A

- Chagall

M

- Charlier

J

- Cipriani

- Collaert

A

- Collaert

J

- Coornhert

D V

- Corinth

L

- Cort

C

- Coubine

O

- Craig

E G

- Crépin

S

- Daglish

E

- Daumier

H

- Davis

W

- Degner

A

- Dillon

H P

- Dolendo

Z

- Domenichino

- Duez

E A

- Dumont

M

- Dunstan

B

- Dürer

A

- Dyck

A van

- Fairclough

M

- Fairclough

W

- Fantin-Latour

H

- Floris

F

- Foujita

T

- Galle

C

- Ghisi

G

- Gibbings

R

- Gill

E

- Goltzius

H

- Greiner

O

- Gromaire

M

- Groome

E

- Haarlem

C C van

- Heckel

E

- Heemskerk

M van

- Heise

W

- Hermes

G

- Hettner

O

- Hill

F

- Hill

V

- Hofmann

L von

- Holroyd

C

- Hudson

E E

- Hughes-Stanton

B

- Ingres

J A D

- Jacquard

A

- Janinet

J F

- John

A

- Jou

L

- Kapp

H

- Kennington

E

- Klinger

M

- Knight

L

- Laboureur

J E

- Larson

C

- Laurent

E

- Lawson

R

- Legrand

L

- Lehmbruck

W

- Lepère

A

- Lippy

- Lucas

van Leyden

- Lurçat

J

- Lyubavin

A

- Maillol

A

- Mander

K van

- Marchand

J

- Maratta

C

- Master

of the Die

- Maetzel-Johannsen

D

- Mellan

C

- Michelangelo

- Michl

F

- Moore

T Sturge

- Mueller

O

- Nash

J

- Neuschul

E

- Nevinson

C R W

- Palma

J

- Peruzzi

B

- Paerels

W

- Pechstein

M

- Perret

P

- Philipp

M E

- Philippi

R

- Philips

- Picasso

P

- Raimondi

M

- Raphael

- Reeve

R

- Regnault

N F

- Rembrandt

- Rodin

A

- Rowlandson

T

- Rubens

- Saenredam

J

- Shannon

C H

- Sims

C

- Sloan

J

- Sompel

P van

- Strang

W

- Strohmeyer

H

- Tissot

J J

- Vaga

P del

- Valadon

S

- Veneziano

A

- Verkolja

N

- Vieillard

R

- Vos

M de

- Whistler

J M

- Wierix

J

- Williams

G

- Zadkine

O

- Zorn

A

Return to the top |