|

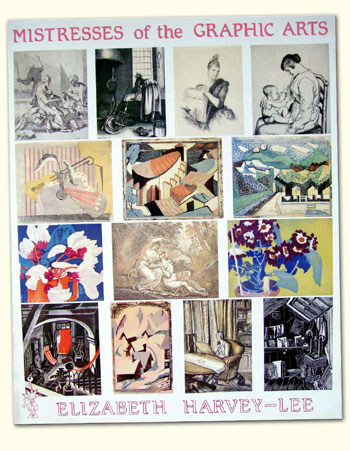

MISTRESSES

OF THE GRAPHIC ARTS

Famous & Forgotten

Women Printmakers c1550 – c1950 Famous & Forgotten

Women Printmakers c1550 – c1950

Though it comes as no surprise to discover that European

women have been engaged in artistic activity from time

immemorial, it is perhaps remarkable that they have been

printmakers almost since the inception of woodcut and

engraving in the late 14th century. Printmaking, especially

the intaglio techniques (and the later invention of lithography)

requires highly specialised equipment and materials such

as presses, tools, acid, and involves manhandling heavy

sheets of copper (or weighty blocks of limestone).

The distaff side of the history of printmaking is shaped

by these requirements.

The

earliest women printmakers were nuns. Life in a convent,

without the personal commitments of family life and

household organisation of the lay woman, allowed time

and financial support to produce prints. The need for

illustrations in religious books and for duplicated

holy images to sell to pilgrims supplied a motivation

that encouraged the making of woodcuts. Fruit wood blocks

are soft enough to cut with a knife and hand pressure

is sufficient to print them. The resulting simple outline

images could then be hand-coloured. By the 15th century

convents, like that of Marienwater in the Netherlands,

are known to have acquired screw printing presses to

print both text and pictorial woodcuts.

It was not till the 16th century that women apparently

became involved in intaglio copperplate engraving, but

from the beginning they are recorded by name rather than

being anonymous like their wood cutting sisters. Diana

Scultori working in Italy in the latter half of the 16th

century was the first significant female engraver. In

general, like Diana Scultori, women engravers were all

daughters from printmaking families and like as not married

to engravers or painters too. They had grown up in printing

studios and the equipment and technical assistance was

to hand. Most of the early women engravers were collaborative

or interpretative engravers, assisting the male members

of their families or reproducing the designs of their

fathers, brothers, husbands or other artists. The engravings

of women at household tasks by Geertruyd Roghman in the

early 17th century are perhaps the first original engravings

by a woman being carried out to her own designs. However,

until the 19th century, the majority of women continued

to work as reproductive engravers.

On the other hand women etchers, in keeping with the

freer more painterly traditions of the medium, are more

generally original printmakers. Etching did not have

a wide following until the 17th century and had its roots

in Italy, so that it is fitting that the first important

woman etcher is the 17th century Italian painter Elisabetta

Sirani.

Through

the 18th century several women, like Angelica Kauffmann,

became celebrated artists and the number of women

involved in printmaking increased considerably. In

addition to professionally trained artists and craftswomen

it became a fashionable pursuit for the educated leisured

classes, among aristocratic and royal dilettanti, who

had sufficient money to pay for professional help and

guidance. Angelica Kauffmann was one of only two women

elected to the newly founded Royal Academy in London,

though she would contribute paintings rather than her

prints to the Academy exhibitions. In Revolutionary

France the Salon was opened to women and by 1808 one

fifth of the exhibitors were women so that it was nicknamed

the Woman’s Salon.

In

England the painter Joseph Farington commented on knowing

a circle of women artists who made their living copying,

painting miniatures or engraving and teaching engraving,

though Letitia Byrne complained to him that “there

is a prejudice against employing women engravers”.

Women were amongst the earliest exponents of lithography

when it was invented in 1798. Lithography allows the

most natural drawing of any of the traditional printmaking

techniques, whether on stone or even more so, on transfer

paper. Lithographic printing on the other hand is complex

and commercial lithographic studios were set up from

the start to which amateurs and trained artists alike,

whether male or female, could repair to have their images

printed. Women were amongst the earliest exponents of lithography

when it was invented in 1798. Lithography allows the

most natural drawing of any of the traditional printmaking

techniques, whether on stone or even more so, on transfer

paper. Lithographic printing on the other hand is complex

and commercial lithographic studios were set up from

the start to which amateurs and trained artists alike,

whether male or female, could repair to have their images

printed.

By

the later 19th century it was not unusual for women

to take up art professionally. In England The Society

for Female Artists was founded in the 1850’s and

had a school to train women. The Etching Revival gave

impetus to original printmaking and specialist intaglio

printers, such as Goulding in London, Delâtre in

Paris and Felsing in Berlin, opened printing studios.

This and the establishment of Art Colleges with printing

facilities and tuition enabled a wider range of women

to take up printmaking, though they tended largely to

come from the professional middle and upper classes,

who could afford the fees. London University’s

Slade art school was the first London art school to admit

women on equal terms.

From

the 1880's women artists of international

stature, such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot in France

interested themselves in printmaking and in Germany Käthe

Kollwitz made it her primary mode of expression.

England,

more than any other country, saw a surge in output

of graphic art among women art students in the early

years of the 20th century. Through the Etching Boom,

1900-1930, successive generations specialised in etching

at the Engraving School of the Royal College of Art

under the guidance of first Frank Short and Constance

Pott and later Malcolm Osborne and Robert Austin. The

Slade School produced more Modernist painters who also

had a related interest in etching. The Central School,

with the classes of Noel Rooke and Leon Underwood’s

school, had a bias towards wood engraving.

Women

students took to wood engraving in seemingly huge numbers;

many of the greatest names in British wood engraving

are women, Gwen Raverat, Clare Leighton, Gertrude Hermes.

In the 1920's and 1930's the alternative

relief printing technique of colour woodcut had several

leading women practitioners. With the Etching Crash at

the end of the 1920's the disappearance of a market

for black & white prints encouraged the making of

colour prints not only from wood blocks, but in etching

(Elyse Lord, Winifred Austen) and particularly in linocut.

In Claude Flight's classes on linocut at the Grosvenor

School the majority of his students were women. Fewer

women (as indeed fewer artists at all) took up lithography.

Many women only exhibited while they were still students

or in the years immediately following their studies and

then disappear without a trace.

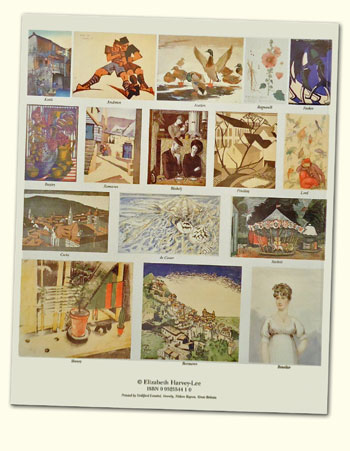

Published 1995

124 pages. 361 prints described and illustrated in b/w

(30 also reproduced in colour on the front and back

covers)

(UK

Price: £15, International orders: £20)

Special

Offer

Purchase

the two catalogues; Mistresses and Unsung

Heroines, together for £27 (UK) or

£35 (International).

See

also the catalogue entitled Eve.

^ Return to the top of this page ^

|