|

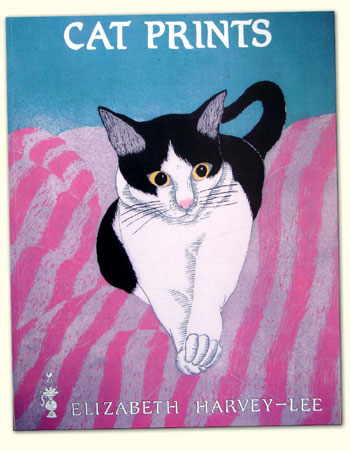

CAT

PRINTS

Graphic

images of Cats, Graphic

images of Cats,

prints from the

16th – 20th Centuries

Though

traditionally the cat has been held to be the ‘familiar’ of

witches, it might equally be so described in relation

to artists. Erasmus Darwin wrote To respect the cat

is the beginning of the aesthetic sense, while Desmond Morris

observed Artists like cats; soldiers like dogs and in

the opinion of Leonardo da Vinci The smallest feline

is a masterpiece. The American Pop artist Robert Indiana

noted After all, a cat and art are only two letters

removed.

One feels when artists include a cat in their compositions,

or make the cat their specific subject, that the cat

portrayed is a part of their household.

It

is strange that P G Hamerton, an enthusiast for etching

and the graphic arts and a contemporary of Manet, should

have opined It is odd, notwithstanding the extreme

beauty of cats, their elegance of motion, the variety

and intensity of their colour, they should be so little

painted by considerable artists. In terms of printmaking

this claim does not stand up; some of the greatest

printmakers have included cats in their prints, Dürer, Barocci, Bellange,

Callot, Rembrandt, Hollar, Goya, Manet &c. The instance

of cat prints increases sharply from the end of the 19th

century, after Hamerton made his comment.

Cats

appear in prints before the end of the 15th century,

very shortly after the invention of the earliest intaglio

technique, line engraving. Their presence, particularly

in Northern Europe where they appear first, is however

at this period generally symbolic. Perhaps the earliest

example of an engraved cat is in Israhel van Meckenem’s

engraving ‘The Visit to the Spinner’, c1495-1503,

which includes a cat resting on the floor in an interior

with a woman sitting spinning accompanied by a man seated

holding his sword by the hilt point-down on the floor

between his feet. From a series formerly considered as

straight-forward scenes of daily life but now interpreted

as expressions of different sorts of love, this image

represents illicit love. The cat was traditionally a

medieval symbol of lust, while prostitutes were nicknamed ‘cats’ and

brothels ‘cathouses’. The presence of the

cat in Meckenem’s engraving points to the reason

for the man’s visit to the woman spinning.

However,

in the 16th and 17th centuries a cat is often included

in prints of general scenes of women spinning without

any overtones of illicit or ‘commercial’ sexual

reference. Girls were taught to spin to fit them for

the virtuous household duties of marriage, hence the

term ‘spinster’ for an as yet unmarried woman.

The

visual symbolism associated with cats is complex and

sometimes contradictory, reflecting various aspects

of their innate characteristics and not just feline

sexual proclivities. Their greed for food and lack

of guilt at stealing it saw them included in kitchen

scenes. Brueghel’s ‘Rich

Kitchen’, engraved by Pieter van der Heyden in

1563 has a cat, while the ‘Poor Kitchen’ is

without. Their nocturnal habits suggested night and darkness

and by association evil, the Devil and witchcraft; but

equally sleep. Despite this bad press and often being

only grudgingly valued as pest controllers, the quiet,

self-contained, contemplative, companionable nature of

the cat also occasionally attracted old master printmakers’ attention.

A cat reposing or curled up asleep emanates security

and the comfort of home and hearth and invites being

drawn.

The

Italian School seem most open to this domestic aspect

of the cat’s nature. A delightful little etching

by Giulio Campagnola, c1515, shows a fat baby seated

on a step whispering into the ear of one of a group of

three fat cats sitting on a ledge. Eneo Vico’s

engraving of the 'Academy of Baccio Bandinelli', c1552,

has a cat at the feet of the apprentices who sit drawing

in front of the fire. Federico Baroccio included a sleeping

cat curled up on a chair in the corner of his ‘Annunciation’ etched

c1585. When Goltzius engraved his series of ‘The

Life of the Virgin’, 1593, his master-pieces in

imitation of six great masters, he included a less innocent

cat on a window sill springing up to catch a bird between

it front paws in ‘The Holy Family’ engraved

in imitation of Baroccio. Several other prints of the

holy family include an incidental cat. Jacques Bellange

shows a cat beside the cradle in his ‘Virgin and

Child with a Cradle’, c1600-1610. Rembrandt’s

friend Ferdinand Bol, c1645, and Rembrandt himself, 1654,

both etched the holy family in interiors with an attendant

cat. The cat is nowhere mentioned in the Bible but from

the 16th century is portrayed in biblical subjects, particularly

those given a contemporary interior setting.

In

the mid-17th century appeared two prints which are

exceptions to the general old master sidelining of

cats. Wenceslaus Hollar and Cornelis Visscher each

portrayed a cat as the specific subject of a print

(catalogue items 6 & 9), though even here Hollar’s cat is surrounded

by the inscription It’s a good cat that doesn’t

steal tidbits and the setting by a grating with the cat

oblivious of the mouse behind him in the Visscher engraving

suggests the possibility of an ulterior, hidden meaning. In

the mid-17th century appeared two prints which are

exceptions to the general old master sidelining of

cats. Wenceslaus Hollar and Cornelis Visscher each

portrayed a cat as the specific subject of a print

(catalogue items 6 & 9), though even here Hollar’s cat is surrounded

by the inscription It’s a good cat that doesn’t

steal tidbits and the setting by a grating with the cat

oblivious of the mouse behind him in the Visscher engraving

suggests the possibility of an ulterior, hidden meaning.

Emblem

books had been popular since the later 16th century

with their moralising images which had several layers

of meaning. Cats (in an age before neutering) featured

in these illustrations usually as the subjects of amorous

aphorisms. Cats also appeared in printed illustrations

to popular collections of satirical fables, “Reynard

the Fox”, the “Fables” of La Fontaine

and their prototype Aesop’s “Fables”.

Pictorially cats lend themselves well to anthropomorhism

and were also treated in this manner in independent prints

(items 14,22,29).

The

illustrations (items 10,11) to Count Buffon’s “Natural

History”, the first encyclopaedia of the animal

world, from the later 18th century, anticipated a new

interest in cats as print subjects in their own right;

a move from the cat as symbol to the cat as model. Gottfried

Mind in the early 19th century was the first artist to

dedicate himself to the cat as a theme. In admiration

of his skill and observation, capturing cats in action,

at play, fighting, as well as at rest, his contemporaries

gave him the sobriquet Raphael of the Cats. Though not

himself a printmaker, publishers commissioned engravers

to etch his drawings and watercolours (items 17-20).

Queen

Victoria helped to make cats fashionable pets. She

kept Persians. Pasteur’s publication in 1865

on the transmission of diseases and the benefits of hygiene

further contributed to the cat’s elevation from

the kitchen to the drawing room; feline cleanliness and

fastidiousness being their passport. The growing popularity

of cats in middle class homes led to a demand for decorative

pictures and prints of cats (items 23-26).

Artistically

the cat came into its own in fin de siècle France

(one of the Montmartre cabarets was called Le

Chat Noir, The Black Cat, and published a periodical

of the same name whose pages were decorated with images

of cats by notable artists of the day). Cat prints proliferated

throughout Europe in the early decades of the 20th century.

Published

2000

64 pages, 126 items described and illustrated in black & white, 8 in colour.

(UK

Price: £10, International orders: £15)

|

|

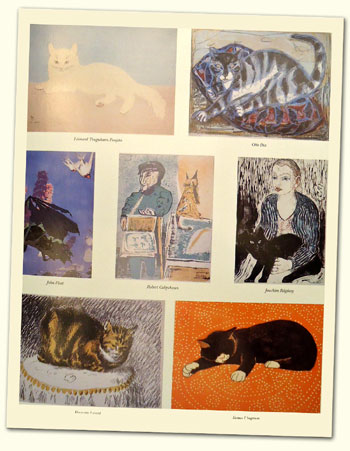

Artists

included in the catalogue:

- Aldous

W

- Allingham

H

- Anderson

S

- Baer

M

- Baquoy

J C

- Berger

G

- Bloemaert

C

- Bloemaert

F

- Bodmer

K

- Bonnard

P

- Bresslern-Roth

N von

- Brightwell

L R

- Bodribb

G M

- Brooks

M

- Brueghel

P

- Callet-Carcano

M

- Cardon

A

- Chahine

E

- Colley

W F

- Colqhoun

R

- Couché J

- Delaune

E

- Detmold

E J

- Dix

O

- Dodd

F

- Dunoyer

de Segonzac A

- Elstrack

R

- Foujita

L T

- Frood

H

- Gill

E

- Gill

P

- Girdwood

S

- Goeneutte

N

- Goya

F

- Grant

D

- Green

A

- Green

G

- Halm

P

- Hamilton

I

- Hamson

T D

- Harvey

J H

- Hegi

F

- Hollar

W

- Hughes

P

- Kempster

A B

- Komjáti

J

- Lambert

P

- Laprade

P

- Legrand

L

- Lempereur

L S

- Lindsay

L

- Loevy

E

- Manet

E

- May

E G

- McEntee

D

- Menpes

M

- Miel

J

- Mind

G

- Monogrammist

DAC

- Morgan

G

- Morisot

B

- Murray

C O

- Muyden

H van

- Nash

J

- Nash

P

- Nemes-Ransonnet

E

- Niekerk

S

- Paterson

V

- Petterson

M

- Phipps

H

- Pimlott

P

- Platt

J

- Plückebaum

M

- Possoz

M

- Prevost

B I

- Rágóczy

J

- Reiner

I

- Rowlandson

T

- Royds

M

- Schenau

J F

- Sève

J de

- Simpson

J

- Smallfield

F

- Steinlen

T A

- Stiles

S

- Tavener

R

- Teniers

D

- Thomas

M F

- Tournour

M

- Turner

L

- Utagawa

T

- Vegter

J

- Vernet

C

- Visscher

C

- Zorin

L

Return to the top |