|

THE

SEDUCTIVE ART

|

The

British Passion for Etching 1850-1950

A

visual summary of a century of British etching

through the Etching Revival and Boom years.

Produced

in the form of a stock catalogue, with entries

for 350 artists, organised by ‘school’ and

association, in chronological sequences.

A

Preface (reproduced below) is followed by 25 ‘chapters’,

each generally with a short introductory essay.

The titles of these ‘chapters’ are

listed below under the heading Contents. |

Contents

Forerunners & immediate

Precursors: The Etching Club

The Founding Fathers – Whistler, Haden and

their Circle

Foundation and early years of the Royal Society of

Painter-Etchers (R E)

Early Members of the R E 1880-1900 – Minor

Etchers

Early Members of the R E 1880-1900 – Pioneers

of the Modern British etching Tradition

Non-Members of the R E 1880-1900

Slade students under Legros 1876-1892

Royal College of Art students under Short 1891-1924

Slade students 1892 to the Great War

The Sickert Circle – Pupils of Sickert

Bolt Court students 1910-1915

Independent etchers 1900-1920

The Naturalists – Etchers of Birds 1900-1930

Birmingham Friends

The 1920’s. The height of the Etching Boom

Slade students 1920-1930

Independent etchers 1920’s-1930’s

Royal College of Art students under Osborne & Austin

1924 -1940

Goldsmiths’ College Group

Rome Scholars

Painters who take up etching in the Boom years of the

1920’s

Wood Engravers who also engraved on Copper in the Boom

years

Minor etchers of the Boom years 1920’s-1930’s

The Last Generation. New etchers & engravers 1930-1950

Scottish Etchers 1890’s-1930’s

Colour Etching 1890’s-1940’s

End Word

Appendices

The Society of Graphic Art

The Society of Graver Printers in Colour

Bibliography

Index of Etchers

THE SEDUCTIVE APPEAL OF ETCHING

Surprisingly,

as early as 1710 in Susannah Centlivre’s

play 'The Man is Bewitched', Lovely’s invitation

to Maria to withdraw together to another room, is cloaked

in the propriety of viewing a collection of prints

in a connotation that anticipates the more recent ‘line’ “Come up and see my etchings ”.

However,

this memorable if somewhat dubious expression was

born of the very genuine passion for etching prevalent

at the end of the 19th century and in the early decades

of the 20th. Hugh Walpole in his novel 'Portrait of

a Man with red Hair' captures this intense period enthusiasm

in the following exchange.

Have you ever felt the collector’s passion

yourself ?

I

have always loved prints very dearly, etchings

especially … Etchings

are intimate and individual as is no other form of graphic art. They are so

personal that every separate impression has a fresh character. They are so

lovely in soul that they never age nor have their moods …

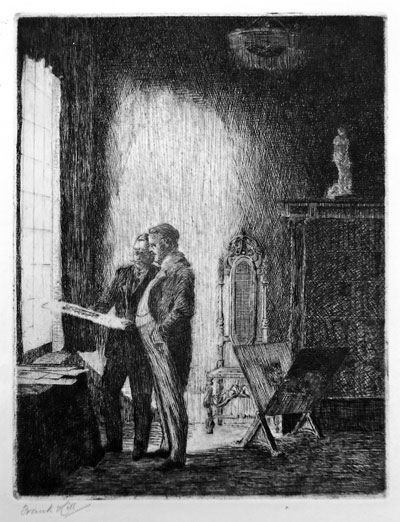

Frank

Short, a seminal figure in the British Etching Revival

and Boom, expressed the pleasure of sharing prized

etchings with friends in a booklet for the Royal

Society of Painter-Etchers in 1911. Short’s

description of a palpable sensual delight in physically

handling etchings as well as an emotional and intellectual

response to the images finds a visual equivalent

Frank Hill’s

drypoint "The Etching Connoisseur" (catalogue

item 606, see below).

The

especial delight in prints…that the collector

knows – comes of that intimate intercourse with

the pet proof… (with) prints of your very own

that you take out of their solander case or portfolio;

prints you hold tenderly in your hand, turn into various

lights, and lift from the mount to enjoy the very feel

of the paper: proofs that you have learned line by

line, and yet in which you are always finding new meaning.

Short

wrote both as a collector and as an artist practitioner

of etching. His sensuous delight in etching was shared

by other artists. Samuel Palmer acknowledged his pleasure

in the medium.

O!

the joy – the colours and brushes pitched

out of the window; plates…got out of the dear

little etching cupboard…needles sharpened three-corner-wise

like bayonets.

The

artist Hubert von Herkomer was even more explicit …

twenty

times and more did I give up etching and twenty

times and more did I take it up again. I have burned

holes with acid in my clothes, and holes in my skin;

I have spoiled carpets and had inflamed throats from

pouring over the fumes; I have sat up half the night

with a plate that would not come out right, and had

finally abandoned; I have taken plates to my

bedroom and worked at them half undressed, then gone

to bed and had frightful dreams about them. I have

neglected all duties in the dog-days of my etching

career, have made my family miserable and ill by

filling the whole house with bad fumes; and yet I

live to say that I love etching with all my heart

and soul.

Whistler’s initiation into etching, described

by a fellow young draughtsman at the U S Coast & Geodetic

Survey conveys the etcher’s excitement in the

practical technicalities.

Mr

McCoy, one of the best engravers in the office, went

over the whole process with us – how to

prepare the copper plate, how to put on the ground,

and how to smoke dark, so that the lines made by a

point could be plainly seen. For the first time since

his entry into the office, Whistler was intensely interested… Having

been provided with a copper plate…and an etching

point (needle), he started…his first experiment

as an etcher… After he had finished etching,

I watched him put the wax preparation around the plate,

making a sort of reservoir to hold the acid as McCoy

had instructed, Then he poured the acid on the plate,

and together we watched it bite and bubble about the

line…

A

sensuous interpretation equally pervaded etching

scholarship. Martin Hardie, Keeper of Prints at the

Victoria & Albert Museum, compiler of the catalogues

of several etchers’ work and a keen amateur etcher

himself, in his inaugural lecture to the newly founded

Print Collectors’ Club in 1921, contrasted the

characteristics of the two greatest formative influences

on British etching in the boom years of the 1920’s,

Rembrandt and Whistler, in the following analogy.

I

regard them as the Jupiter and Venus, largest and

brightest among the planets in the etcher’s heaven – Rembrandt

the Jupiter, because he is the more forceful and masculine,

with a brain powerful and masterful, penetrating in

its perception of character, wide and deep in its emotions;

Whistler the Venus, because, with all his mastery of

the medium, his significance of expression, he has,

in a marked degree, the predominant feminine qualities

of intuition, quick insight, delicacy, refinement,

daintiness – shall we say, too, of charming unexpectedness

and caprice?

THE PARTICULARLY BRITISH ENTHUSIASM FOR ETCHING

In

1862, when the Etching Revival was scarcely under

way, the French poet and art critic, Charles Baudelaire,

commented on the British craze for etching.

Professional artists had founded The Etching Club in

1838 and amateurs such as Queen Victoria and Prince

Albert indulged an interest. But it was from the 1880’s

that British artists’ and collectors’ involvement

with etching really escalated. P G Hamerton published

books and periodicals devoted to etching; Francis Seymour

Haden founded the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers

and established annual exhibitions of members’ etchings.

Etching was introduced into the curriculum of the recently

established London art schools, the Royal College of

Art and the Slade.

The

popularity of etching in Britain reached its zenith

in the second half of the 1920’s , when literally

hundreds of artists engaged in it. An ancillary 'Print

Collectors’ Club' had been set up by the Royal

Society of Painter-Etchers; periodicals such as Print

Collector’s Quarterly kept contemporary etching

in the public’s awareness with illustrated articles

and catalogues raisonnés of etchers’ work

to date. From 1923, for over a decade, Malcolm Salaman

published the annual 'Fine Prints of the Year', which

illustrated fifty new British etchings each year. The

booming market encouraged established painters and

sculptors not trained as etchers to take up the technique.

In

the case of the leading etchers of the day, such

as D Y Cameron, Muirhead Bone, James McBey or Arthur

Briscoe, demand outstripped supply. Editions were

fully subscribed to in advance, so that on publication

impressions could be re-sold immediately at auction

for several times the original subscription price.

By the end of the decade this intrusion of adverse

speculative interest in the print market inevitably

brought about its crash (not helped by the parallel

crash on Wall Street). Many artists stopped etching

when the market disappeared but the continuing allure

of etching as a creative technique still held some

artists in sway through the 1930’s till a more

final hiatus caused by the Second World War. Indeed

Gerald Lesley Brockhurst’s

masterpieces, "Adolescence" and "Dorette", among the

most outstanding images of the modern British etching

tradition, were etched in the early 1930's after

the crash.

A GOLDEN ERA

The

century 1850 – 1950 represents a golden

era in British etching. An instantly recognizable ethos

pervades the works but each artist’s contributions

to the canon carry an autographic individuality like

a personal handwriting. Exponents of an essentially

monochrome art, with the emphasis on the expressive

qualities of line and tone, the etchers of the period

had superb drawing skills. Their etchings reward literal

close study; magnification reveals an abstract microcosm

of lines, flicks, crosshatchings that to the distance

of the naked eye resolve into the familiar town scene,

landscape, marine, animal, bird or figure study or

portrait. Never before or since have so many artists

in a single country at a single period practised the

art of etching. Equally remarkable is the number of

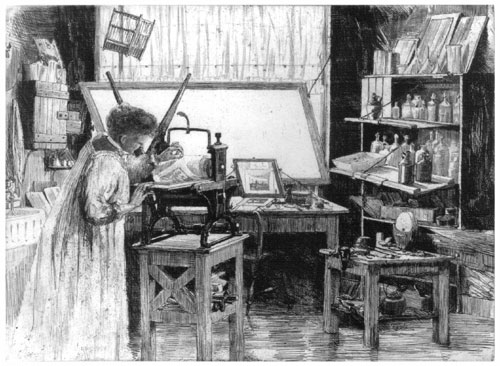

women among their number. Item 149 in the catalogue

(see below), a self-portrait at the press by Constance

Pott (assistant to Frank Short in the engraving school

at the Royal College of Art) gives a fascinating view

of a woman examining a proof as it come off the press

amid all the paraphernalia of the etching studio.

STYLISTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Etching

evinces a flowing graphic line set off by telling

blank intervals but equally has the potential through

a network of crosshatched lines to create a rich,

painterly chiaroscuro of tone. Commensurately it

can be a spontaneous gesture in which the subject

is drawn from nature directly onto the plate, or

a highly finished transcription of a previously worked

out composition. The diversity of approach in Rembrandt’s

plates as his style evolved over the years provided

examples of both alternative approaches. While the

etchers of the 1920’s Boom years availed themselves

freely of both conventions, the pioneers of the etching

Revival, Whistler and Haden, advocated linear immediacy,

which they considered ‘true’ etching as

opposed to the ‘false’ etching of the

highly finished tonal plate worked over its entire

surface. Haden also worked in pure drypoint, Rembrandt

again supplying the model. Drypoint was much favoured

by succeeding generations of British etchers. Aquatint,

unknown to Rembrandt and only invented towards the

close of the 18th century, was rarely used, despite

earlier strong English associations. Although Rembrandt

was the single greatest stylistic influence on modern

British etching, it was contemporary French etching

which instigated the new direction British etching

took in the 1850’s. Whistler and Haden had close

contacts with Parisian etching circles and were instrumental

in the moving to London of Legros permanently and Tissot

for a decade, as well as the visits of the French printer

Auguste Delâtre. The etchings of Millet and Meryon

would influence later generations of British etchers.

HOW

THIS CATALOGUE IS ORGANISED HOW

THIS CATALOGUE IS ORGANISED

The arrangement of the catalogue is roughly chronological,

both overall and within the subsections; the chronology

based on the period when an artist took up etching

rather than the specific dates of the individual items

included. This system is necessarily subject to anomalies

being determined by examples available in my stock.

Many etchers worked through several decades and may

be represented here by an etching carried out twenty

or thirty years after they first started etching.

Where it seemed appropriate, groupings of artists

have been determined by the institution at which they

trained, or according to ethos or friendship, or even

lack of affiliation. As by coincidence several of the

leading etchers were Scots by birth or association,

they have been removed from the general chronological

sequence and included together in a separate section

at the end of the catalogue.

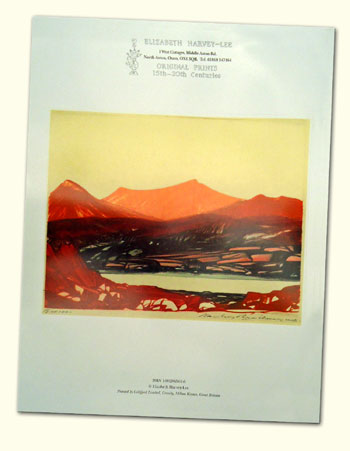

Published 2001 to celebrate the new millennium

384 pages. Entries for 350 artists, organized by ‘school’ and

association in chronological sequences. 783 items described.

830 illustrations in black and white.

(UK

Price: £30, International orders: £35)

^ Return to the top of this page ^

FURTHER

INFORMATION on

an entry in The

Seductive Art

Confusingly there

are two artists called Eric Newton, near contemporaries,

and in The Seductive Art catalogue I have

compounded them.

The

two prints illustrated in the catalogue are by Ernest

Eric Newton,

but the biographical information given in the catalogue

is for another Eric Newton. For further information

please visit the dedicated website for Ernest

Eric Newton.

|