|

UNSUNG

HEROINES

A

further selection of MISTRESSES OF THE GRAPHIC ARTS,

Women printmakers 16th – 20th centuries A

further selection of MISTRESSES OF THE GRAPHIC ARTS,

Women printmakers 16th – 20th centuries

This

collection of prints by women, presented as Unsung

Heroines, complements and supplements the collection

I offered in 1995 as Mistresses of the Graphic

Arts.

As I have concentrated on the inclusion of women printmakers

not represented in the first catalogue and as most

of the ‘famous’ names were

included there, the emphasis here is primarily on less-known

artists. As the involvement of large numbers of women

in printmaking is a 20th century phenomenon, the emphasis

too is very much on women working in the first half

of that century and to a lesser extent in the decade

or so after World War II.

Many

women only produced prints as students or in the years

immediately after they had finished training. Sometimes

a commitment to family life took precedence, or the

disruptive historical events of two World Wars and

the decline in the print market after the Boom years

of the 1920’s,

prevented them from pursuing a career in printmaking

and thus pre-empted the possibility of establishing a

reputation. Their work not being frequently in circulation

it has a freshness and can come as a delightful discovery.

Where

artists are ‘duplicated’ in the new

catalogue, they are represented by different images,

sometimes worked in different media, to those in Mistresses… .

The entries for these artists supply only additional

or fuller information, amendments for instance of dates

where new information has come to light. Item numbers

in the Mistresses catalogue are referenced and the main

biographical details supplied initially in Mistresses are not repeated, the two catalogues ‘working’ in

tandem. A general chronological progression pertains

in Unsung Heroines too but in this case generally within

a sub-group determined by the print process used by the

artist.

No doubt being British and being based in England has

determined the bias towards British women artists or

could it be that there are more British than Continental

women active as printmakers at this period? A reversal

of the situation characteristic of earlier centuries.

On the Continent in the 16th and 17th centuries the

few women active as engravers tended to belong to printmaking

families and grew up in the tradition. In England where

a native tradition was slower to be established, women

did not begin to make prints until the 18th century.

The

18th & 19th centuries, particularly in continental

Europe, witnessed a large increase in the numbers of

women involved in printmaking, as in the practice of

the arts in general.

The

pioneering collection of women’s

prints put together by Henrietta Louisa Koenen 1848-61

and added to in the following two decades by her husband,

the director of the Amsterdam Print Room, is an indication

of this surge in female printmaking activity. It comprises

some 507 prints by 284 different artists.

Of

these 284 women engravers, only 9 are from the 16th & 17th

centuries – Diana Ghisi/Scultori) of Mantua; Marie

de Medici; Magdalena van de Passe; Geertruyd & Magdalena

Roghman; Elisabetta Sirani; Teresa del Po; and Susanna

Maria von Sandrart.

Reflecting

the general history of printmaking, they are

mainly Italian or Dutch. Reflecting

the general history of printmaking, they are

mainly Italian or Dutch.

Of the 275 18th & 19th

century women printmakers listed, the vast majority

are French, or of Germanic origin, with a very

occasional Dutch, Swedish, or Spanish representative.

Several are aristocratic or royal amateurs but

many are professionals.

Fifteen

only are British – Leticia Byrne; Maria Cosway;

Lady Dashwood; Elizabeth Ellis; Lady Louisa Augusta Greville;

Mrs Eliza B Gulstone; Elizabeth Judkins; Clara Montalba;

Mary Ann Rigg; Lady Elizabeth Rutland, née Howard;

Miss Sardsam; Mrs Dawson Turner, née Mary Palgrave,

and one of her five daughters, Miss Turner; Queen Victoria;

and Caroline Watson. Fifteen

only are British – Leticia Byrne; Maria Cosway;

Lady Dashwood; Elizabeth Ellis; Lady Louisa Augusta Greville;

Mrs Eliza B Gulstone; Elizabeth Judkins; Clara Montalba;

Mary Ann Rigg; Lady Elizabeth Rutland, née Howard;

Miss Sardsam; Mrs Dawson Turner, née Mary Palgrave,

and one of her five daughters, Miss Turner; Queen Victoria;

and Caroline Watson.

A

further three prints, by the American artist Mary Cassatt,

were added when the collection was acquired by an American,

a member of the Grolier Club, and presented to the New

York Public Library in 1900. The entire collection was

exhibited at the Grolier Club in 1901, with a catalogue

entitled Collection of Engravings, Etchings and Lithographs

by Women. A

further three prints, by the American artist Mary Cassatt,

were added when the collection was acquired by an American,

a member of the Grolier Club, and presented to the New

York Public Library in 1900. The entire collection was

exhibited at the Grolier Club in 1901, with a catalogue

entitled Collection of Engravings, Etchings and Lithographs

by Women.

In

the 18th century, because of the prevailing proprieties,

women were not admitted to academy schools, where life

drawing from the male model was central to academic

training. Neither Angelica Kauffmann nor Mary Moser,

although elected Academicians, were able to take advantage

of the Royal Academy’s life classes. In Zoffany’s

group portrait of the assembled members in the Life

Room, mezzotinted by Richard Earlom in 1772, the two

women members are not represented in person but by

their portraits hanging on the wall.

In

Paris women were not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux

Arts, the school associated with the French Academy,

initially founded by Louis XIV in 1648, even after

the égalité of

the French Revolution. They only gained entrance to the

Beaux Arts in 1897. Only French nationals were able to

attend and the many foreign students, drawn to Paris

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, went to the

Académie Julian, where women were admitted from

1880, or to individual artist’s studios. In

Paris women were not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux

Arts, the school associated with the French Academy,

initially founded by Louis XIV in 1648, even after

the égalité of

the French Revolution. They only gained entrance to the

Beaux Arts in 1897. Only French nationals were able to

attend and the many foreign students, drawn to Paris

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, went to the

Académie Julian, where women were admitted from

1880, or to individual artist’s studios.

In

England women of the 18th and 19th centuries were trained

at home by their fathers, such as William Byrne, at

the artisanal level or by a senior artist such as Edwin

Landseer, for instance (see Appendix), who taught several

aristocratic young women to etch. Whereas engraving,

etching and lithography would not have been in the

prospectus of the early Academy Schools, even had women

been admitted as students, as an applied art in relation

to pottery, fabric and book production it would probably

have been taught at the first Victorian government

art schools established to further national industrial

design. The first School of Design in London, 1837,

renamed the National Art Training School in 1857 and

subsequently renamed again in 1896 the Royal College

of Art, certainly taught printmaking at least as early

as the 1870’s. The

presence of female students is apparent from the 1890’s

when Frank Short was put in charge of the engraving school

at the Royal College and had as his assistant, Miss Constance

Pott. In the first three or four decades of the 20th

century, as a post graduate school, the R C A performed

a seminal role in training etchers of both sexes, though

male students outnumbered females.

At

this same period London’s Central School of

Arts & Crafts, founded 1896, was most associated

with training wood engravers, under the tutorship of

Noel Rooke who introduced wood engraving to the curriculum

of the department of Illustration in 1912. In the Central’s

archive of wood engraving students up to 1950, fifty-nine

out of a total of a hundred and fifteen are women. Etching

was also taught at the Central.

The Slade School, founded 1871, perhaps because it mostly

did not have a formal printmaking department, produced

fewer, more idiosyncratic printmakers, such as Eve Kirk

and Edna Clarke Hall.

Of

the smaller private art schools in the capital, established

in the 1920’s, those most associated with women

students of printmaking are Leon Underwood’s school,

known especially for wood engraving (Gertrude Hermes

being one of the most acclaimed students), and the Grosvenor

School of Art, noted for the colour linocut, where women

students out-totalled the men.

Morley Fletcher pioneered colour woodcut in the Japanese

manner at University College, Reading 1898-1906 and at

Edinburgh College of Art, which he directed 1908-23 and

where he invited Mabel Royds to teach colour woodcut

from 1910. John Platt also inspired his students in woodcut,

inviting the Japanese colour woodblock artist Urushibara

to demonstrate to his students in Leicester, where he

was principal 1923-29. He had a number of female students

of colour woodcut, such as Meryl Watts, when he moved

to Blackheath School of Art, 1929-39.

Printmaking

was only rarely taught in provincial art schools before

the 1920’s or ‘30’s.

An exception was Bristol, where Reginald Bush was principal

1895-1934. As a student Bush had won an engraving scholarship

to the Royal College of Art. An impressive number of

female etchers are associated with Bristol (see Nora

Fry, item 53, and subsequent listing). Susan Crawford

taught etching at Glasgow School of Art from 1893 till

1917. Glasgow School of Art, like the R C A in London,

had begun as a government school of design, in the 1840’s.

The

possibilities for public exhibition of women’s

prints developed slowly, from the second half of the

18th century onwards. In England Angelica Kauffmann was

a founder member of the Royal Academy in 1768. She was

one of two women painters among the thirty-six artists

named in the Instrument of Foundation, which restricted

membership to forty Academicians in all (later enlarged

to forty academicians and forty associates, ultimately

to 80 Academicians when associate membership was done

away with). Initially specialist engravers were denied

membership but in 1770 six associate engravers were admitted.

In 1853 at the request of Queen Victoria two of the six

were permitted to be elected as full R A s. In 1921,

by when artists’ original printmaking had superceded

professional reproductive engraving, the separate engraving

category was dropped. Today eight of the eighty Academicians

should be printmakers.

After 1768 no further women artists were elected to

the Royal Academy until 1922. Laura Knight was elected

in 1927. But it was only in 1963 that a woman whose primary

medium was printmaking (Gertrude Hermes) was elected

as an Associate. Equally it may be noted that in the

same period few male printmakers had been elected either.

From

its foundation in 1880, the Royal Society of Printmakers

(R E) welcomed women members (the 1880 Married Women’s

Property Rights law meant that women could take equal

financial responsibility). However it was not till

2003 that a women was elected president (Anita Klein).

But so was her successor, Hilary Paynter.

The

Senefelder Club, set up in 1908 to promote lithography

as a creative medium, also included women from the outset.

This was also the case with the Society of Graver-Printers

in colour, for both colour etchers and colour woodblock

artists; with the Colour Woodcut Society, founded in

1920; and with the London Society of Painter-Printmakers,

1948.

America

led the way in the interest in exhibitions devoted

to women printmakers. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts

held an exhibition of American Women Etchers in 1887,

comprising 388 etchings by twenty-two artists. An expanded

exhibition in New York the following year showed 513

etchings by thirty-five women. The introduction to

the catalogue of this Union League Club exhibition

commented that women had “established their right to be judged

in the same temper and by the same standards as their

bretheren”. In the Women’s Building of the

1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, nineteen women

etchers, including Mary Cassatt, were exhibited by the

dealer Keppel.

North

America was also to the fore in early providing specific

training for women artists. The Philadelphia School

of Design for Women was founded in 1844. By the 1880’s

it taught etching as well as wood engraving, painting,

china decoration and illustration. Emily Sartain, daughter

of one of the founders, the engraver and illustrator

John Sartain, was principal of the school for thirty-three

years, 1886-1919. In New York the Cooper Union Free

Art School for Women opened in 1854 and the Art Students

League in New York accepted women from 1875. Many American

women printmakers also travelled to Europe and especially

to Paris for further training.

Women

have expressed themselves in all the different print

processes, although in common with their male peers,

they have been less drawn both towards lithography

and mezzotint. However, this said, women (in England – Lady

Cawdor and a Miss Waring) were quite exceptionally in

the vanguard as regards experimenting with lithography

at the beginning of the 19th century when the newly invented

technique was first promoted to artists. And at the same

period women took to soft-ground etching because of its

similar immediacy of drawing. In the 18th century Caroline

Watson, daughter of the celebrated mezzotint engraver

James Watson, practised mezzotint professionally, as

did another pupil of Watson, Elizabeth Judkins, but they

are the exceptions that prove the rule. In the 20th century

mezzotint has had few followers among either sex. In

America Emily Sartain was described as “the world’s

only woman artist in mezzotint”; in England women

students or associates of the Royal College of Art very

occasionally essayed mezzotint. Constance Pott and Hazel

Harrison each engraved at least one plate in mezzotint.

After the 17th century women infrequently engraved even

in line; Elizabeth and Letitia Byrne were among the few

to do line engraving on steel plates, a new matrix introduced

at the beginning of the 19th century, rather than the

conventional softer copper. Very few women engraved in

stipple; Caroline Watson was again an exception, as was

Marie Anne Bourlier. Letitia Byrne complained to fellow

artist Joseph Farington, who knew a circle of women artists

who made a living from copying, painting miniatures,

engraving or teaching engraving, that “There is

a prejudice against employing women engravers ”.

As

is also the case with their male counterparts, hard

ground etching was the preferred medium of the greatest

number of women printmakers. However out of the hundreds

of late 19th century and early 20th century women etchers

only three or four have achieved wide recognition and

international acclaim., Mary Cassatt, Käthe Kollwitz,

Suzanne Valladon, Laura Knight. In a specifically British

context one can add Winifred Austen, Elyse Lord and Orovda

Pissarro to the list. Women would seem to use drypoint

only rarely.

Wood engraving and the other relief printing techniques,

woodcut and linocut, have had fewer practitioners in

general of either sex. But, particularly in Britain and

America, a much larger percentage of those who are acclaimed

in the medium are women, Gwen Raverat, Clare Leighton,

Agnes Miller Parker, Gertrude Hermes, Monica Poole, Sybil

Andrews, Elizabeth Keith, Mabel Royds, Lill Tschudi,

Norbertine von Bresslern-Roth.

It

is noticeable in a large group of prints by women,

such as that offered here, that colour is prominent

and almost certainly more so than it would be in a

commensurate group by male artists. Women made strong

statements through colour etchings and aquatints, colour

woodcuts, colour linocuts, colour wood engravings and

colour lithographs, as witnessed in the work of Sybil

Andrews, Audrey Bridgman or Viola Paterson amongst

others; these are a long way from pretty prints of

flowers or birds traditionally expected from the ‘weaker’ sex.

Traditionally

denied access to the live nude model, before the 20th

century women artists specialised in what

were judged the minor subjects – flowers and still

life, portraits, animals, intimate genre scenes – rather

than the grand and usually large-scale history and mythological

subjects prized by the Academies. But there were always

exceptions; and particularly among women printmakers.

To a contemporary audience brought up in a post-impressionist

ethos, the consideration of such a tyranny as a hierarchy

of subject matter is as irrelevant and alien as the medieval

concern of how many angels can perch on the head of a

pin. It is the quality and interest of the individual

work not the category of its subject matter that is of

over-riding importance. 20th century women printmakers

have treated as broad a range of comparable subject matter

as their male fellows.

In

the 16th & 17th centuries because women practitioners

were exceptionally few in number they excited comment

and praise in direct relation to their sex. Vasari was

astounded to discover the young Diana of Mantua; adulatory

poems were addressed to Magdalena van de Passe. By the

18th century a greater number of women were involved

in the arts, yet their personal physical attractiveness

and mental esprit were also important contributing factors

to their celebrity, certainly in the cases of Angelica

Kauffmann and Maria Cosway. The growing number of women

printmakers in the 18th & 19th centuries, and especially

in the 20th century after the wide-scale establishment

of national art schools in many leading cities, by and

large ended gender-based criteria in critical discussion

of individual artists.

Good

art is sexless or perhaps rather bisexual, partaking

of the strengths and sensibilities of both sexes. Käthe

Kollwitz wrote “bisexuality is almost a necessary

factor in artistic production; at any rate , the tinge

of masculinity within me helped in my work”. Yet

there is also a consistently female thread weaving through

women’s prints. Familiarity with the sex of the

author of prints by Kollwitz, or Laura Knight, or Angelica

Kauffmann &c precludes a discussion of their femininity

or otherwise. It is among the prints of little-trumpetted

women artists, whose very anonymity does not immediately

proclaim their sex, that the presence of an indefinable

female sensitivity asserts itself, producing in the viewer

a subconscious recognition that the signature reading “A.

Plate” is more likely to be that of an 'Arabella'

or 'Ann' than an 'Andrew' and “M. Block”,

a 'Muriel' or 'Margaret' rather than a 'Malcolm'. But

this does not always follow. In my first Mistresses catalogue

a colour lithograph catalogued as by Phyllis D Lambert

turned out to be by Philip Lambert.

List

of Appendices

Women

practitioners of the Grosvenor School of Linocut

Women members of the Society of Wood Engravers (to whom

should be added Hilary Paynter and Anne Desmet)

Women Members of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers

(1880-1969)

Women contributors to the annual Presentation Plates

for the ancillary Print Collectors’ Club 1927-1982

Women members of the Senefelder Club from

its first exhibition in 1910 until 1934

Other women who exhibited lithographs with the Senefelder

Club 1910-1934

Women winners of the Prix-de-Rome for Engraving from

its inception in1920 until 1966

Women engravers associated with Sir Edwin Landseer

Women printmakers amongst the 70 exhibitors at the first

exhibition of the London Society of Painter-Printers,

1948

And included within the body of the catalogue a list

of women etchers associated with Bristol School of Art

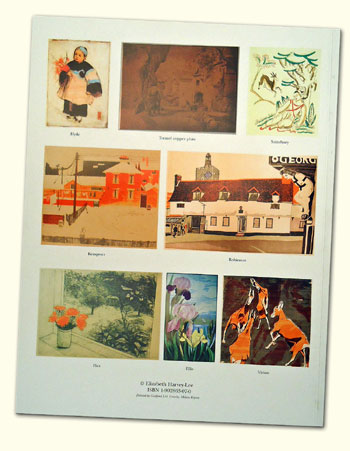

Published

2004

112 pages, 311 items described and illustrated in black & white,

with nine in colour on the cover.

(UK

Price: £15, International orders: £20)

Special

Offer

Purchase

the two catalogues; Mistresses and Unsung

Heroines, together for £27 (UK) or £35 (International).

|

|

Artists

included in the catalogue:

Names

in (brackets) are mentioned but not represented by

prints

- Adshead

A E

- Airy

A

- Amberg

I K

- Andrews

S

- Annesley

M M

- Armitage

J

- Armstrong

E

- (Arnold

H)

- Aspden

R

- Aulton

M

- Bacon

M M

- Bacon

P

- Barnwell

A G C

- Bas R A le

- Baumann

C A P

- Bayley

M

- Begbie

J

- (Bell

V)

- Binyon

H

- Blomfeld

B F M

- Blundel

M L

- Bolingbroke

M

- Bonsey

H E (née Jefferies)

- Boreel

W

- Bradfield

N

- Bresslern-Roth

N von

- Bridgman

A

- Brooks

M

- Brown

E C Austen

- Browne

H

- Bruton

M B

- Bull

N

- Burchill

E M

- (Bush

F)

- Butler

M

- (Byrne

E)

- Byrne

L

- Cameron

K

- Cawdor

Lady C

- (Cheese

C)

- Churchill

N

- Citron

M W

- Clausen

A M

- Clarke

Hall E

- Cartwright

J

- Clay

A

- Clayton

K M

- Clements

G de Vaux

- Coke

D J

- Cole

E V

- Cook

G E

- Cosway

M

- Cowland

M G

- Cox

G F M

- Cragg

H

- (Cross

G)

- Curry

E M E

- Dallas

A C

- (Danse

M)

- Danse

L

- Davis

D A

- Denne

C

- Desborough

C I

- (Deschamps

C F)

- Dobson

M S

- Drew

D

- Ellis

I A

- Fairclough

M

- Fanshaw

C M

- (Fanshaw

P)

- Farmer

M M

- Farqharson

M

- Fenwick

K M

- Fergusson

C J

- Fini

L

- Firth

M

- Flax

Z

- Forbes

E

- Fox

M

- Francis

E J

- Fry

N AS

- Gabain

E

- Gág

W

- Galton

A M

- Garwood

T

- George

D

- George

P H

- Ghisi

D

- Gibbs

E

- Gill

J, E or P

- Ginger

P E

- Glazier

L M

- Gouldsmith

H

- Goldthwaite

A

- Green

C M M

- Gribble

V M

- Groch

G

- Grove

M A F

- (Gunton

K)

- (Hale

E D)

- Hall

E Clarke

- Hamblyn-Smith

M A

- Hamilton

I A

- Harper

J

- Harvey

H

- Hassall

J

- Hayes

G

- Hedger

R

- Heriot

R

- Hermes

G

- Hicks

M

- Hodges

P O

- (Housman

C)

- Howard

C

- Hudson

E E

- Hughes

P

- (Hutchings

H)

- Hyde

H

- (Hyde

J)

- Illingworth

A S

- Jacques

B

- (Jebb

K M)

- Jefferies

H E

- (Jefferies

K G)

- Joliffe

M

- Kàdàr

L

- (Kahlo

F – a portrait)

- Kauffmann

A

- Kay

D

- Keeling

G

- Kempster

B (née Bridgman)

- Kimball

K

- Kirk

E

- Kirkpatrick

E

- Klein

E

- Knight

L

- Kollwitz

K

- Koslowska

S de

- Kron-Meisel

C

- Lambert

E

- Landseer

J

- Larking

L M

- Le

Bas R A

- (Lee-Hankey

M née Garner)

- Leighton

C

- Livett

U

- Lock

J

- Lockyer

I de B

- Lowengrund

M

- Lucas

C

- Lucas

M A

- Lum

B

- (Lum

B[C])

- (Lum

P[B])

- Mantuana

D

- Marr

H

- Marston

F

- Martin

M

- Martyn

E King

- Marx

E C D

- Mavrogordato

J M

- McArthur

M

- McCall

J M

- MacKinnon

S

- Mesham

E B

- Minter

M

- Mitchell

M Y

- Montalba

C

- Morisot

B

- Morshead

A

- Münter

G

- Nash

P

- Nathan

P d’A

- Niekerk

S C van

- Noël

D

- (Orovida)

- Parker

A Miller

- Paczka

C

- Passe

M van de

- Paterson

V

- Peck

J

- (Pilkington

M)

- (Pissarro

O)

- Pole

M M

- Possoz

M

- Pott

C M

- Prax

V H

- Quick

H M

- Rankin

A L

- Raverat

G

- Rhodes

M

- Richards

E

- Riollet

M C

- Robertson

J E

- Robinson

M

- Robinson

S

- Rogers

H

- Roome

L

- Rowney

M

- Rudge

M M

- Ryerson

M A

- Sainsbury

H

- Sanders

V C

- (Schurman

A M van)

- Sharp

m F

- Shelley

E

- Sherlock

A M

- Silas

B

- Simeon

M

- Simpson

A

- Simpson

J S C

- Sloane

M A

- Smith

H

- Spowers

E L

- (Stephens

O)

- Story

E J

- Sully

K M

- Sweet

D F

- Syme

E W

- Temple

V L

- Tesarikova

M

- Thomas

M F

- Thomson

L

- Thornton

V

- (Topham

I)

- Torres

O

- Tournour

M

- Traill

J C A

- Tremmel

M

- Troubridge

Lady U

- Tschudi

L

- Turberville

M G

- Unwin

N S

- Van

Niekerk S

- Velde

N van de

- Vivian

N

- Walford

A C

- Walklin

C E

- (Waring

F)

- (Watson

C)

- Watts

Ma

- Watts

Me

- Wells

F

- Whittington

M

- William

A

- Willis

E M

- (Woollard

D)

Return to the top |