|

RESONANCES

Prints rich in Associations Prints rich in Associations

“…there

is no past or future in art. If a work of art cannot

live always in the present it must not be considered

at all. The art of the Greeks, of the Egyptians,

of the great painters who lived at other times, is

not an art of the past; perhaps it is more alive

today than it ever was."

(Picasso)

No

work of art is created in isolation but is related

to the context of its time, to what has gone

before and, with historical hindsight, to what will come

after. Just as the artist’s personality and interests,

determined by what he has seen or what he is remembering,

perhaps unconsciously, will play their part, the viewer

additionally contributes his or her own distinct personal

associations.

The

colour of the wall paper of a childhood bedroom, the

well-known view from the living room window, a

facial similarity to a loved one, the location

of a happy holiday, objects iconic or obscure admired

on museum visits, the prevailing cultural ambience

of a particular period in one’s life, can all

influence and affect how we see and how we relate to

an image.

David Hockney has commented in an interview “The

fact is, we see with memory, which is why none of us

sees the same thing.”

The

affordable price range of prints, makes it possible to

indulge the occasional idiosyncratic personal rapport,

as suggested above, in collecting prints.

Images

that call to mind other images or circumstances, images

made in direct response, as well as those which unintentionally

strike chords of familiarity in the viewer, form an

interesting selection and question the whole concept

of the nature of originality.

Originality

is a contentious term in specific regard to printmaking;

replication of images being seminal to its invention.

From its origins printmaking has been both a means of

reproduction and a vehicle for original creative expression.

This dichotomy and the paradoxical interplay between

these raisons d’être result

in a fascinatingly rich variety in printed art.

A

frequently quoted adage of Picasso (possibly apocryphal)

is “All artists copy, great artists steal”.

Successive generations of artists have regularly borrowed

from one another.

Raimondi,

as well as imitating landscape backgrounds for his

own engravings from Dürer and

Lucas van Leyden, directly copied Dürer’s

woodcuts of The Life of the Virgin as copper

line engravings, causing Dürer to complain to the

Venetian senate. Goltzius, took out a protective copyright

(privilege) with regard to his engraving of The

Standard Bearer, which was being pirated (see

item 151), but in each of his six plates of

the "Life of the Virgin", tours

de force of virtuosity, he himself imitated the

manner of six different artists, including Dürer

and Lucas van Leyden. It is even reported that he removed

his monogram from some impressions and successfully passed

them off as original compositions by Dürer or Lucas.

Emulation

became a creative force.

It

became part of artistic practice to select models from

the masters and combine them into a new original composition.

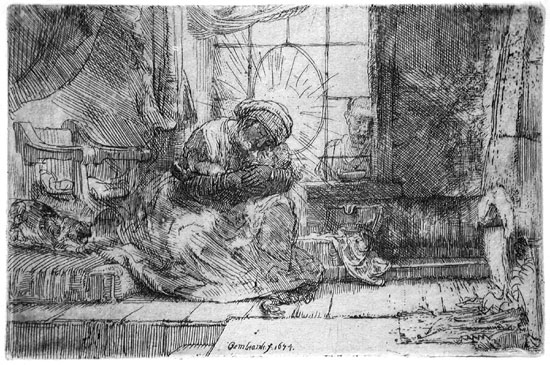

Rembrandt is known to have owned an impression of the

Mantegna engraving of the Virgin and Child from

which he borrowed the pose for his own Madonna in The

Virgin and Child with the Cat and the Snake.

Rembrandt: The

Virgin & Child with the Cat & the

Snake

Original etching, 1654. Ref: Bartsch 63ii/ii (Sold)

In

another etching, Christ driving the Money-changers

from the Temple, Rembrandt took the stance of

Christ, with arm raised holding a scourge, long wavy

locks of hair falling over his back, from a woodcut

of the same subject in Dürer’s Small

Passion series. Copied

onto the plate in the same direction as the Dürer

print, the figure is reversed in impressions of Rembrandt’s

etching. Rembrandt even re-used

a copper plate etched by

Hercules Segers, which he had acquired. Segers’ Tobias

and the Angel was

itself a free imitation in reverse of Hendrik Goudt’s ‘large’ Tobias,

engraved after the painting by Elsheimer. Rembrandt

burnished out the large figures of Tobias and the

Angel at the right and replaced them with a large

clump of trees in front of which the small figure

of Joseph leads the donkey ridden by Mary with

the baby in The Flight into Egypt. Two thirds of

the plate, representing a panoramic landscape,

remain untouched and print exactly as Segers left

the plate.

Raphael’s compositions have been amongst the most

influential in the history of art. A number of them were

based on ancient Roman sculptures. Scholars have identified

the different antique relief carvings on various sarcophagi,

newly unearthed in his day, which were the source of

some of his groupings of figures. Not himself a printmaker

Raphael collaborated with Marcantonio Raimondi, supplying

drawings which Raimondi and his workshop worked up into

finished engravings. Most of the drawings are lost but

through the engravings Raphael’s ideas have been

transmitted to subsequent generations. As late as the

second half of the 19th century Manet would borrow from

a Raimondi-Raphael engraving for the arrangement of his

figures in Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe.

Jacques Villon: colour aquatint of Manet’s Déjeuner

sur l’Herbe.

Manet posed his three principal

figures, his brother Eugène, his future

brother-in-law Ferdinand Leenhoff and the model

Victorine Meurent,

in direct imitation of a Raphael

drawing (now lost) as known to him through

the Raimondi engraving.

He was also inspired in the general concept by

Giorgione’s painting Concert Champêtre.

Among

printmakers the most powerful and recurring influences,

especially as regards British artists, are Rembrandt,

Whistler, Japanese prints, Blake, Palmer and Picasso.

In continental Europe Velasquez and Goya were also

important in this context.

The

prints in the catalogue are largely grouped in order to

correspond with this list.

Of

this listing, Whistler and Picasso, in particular,

were themselves susceptible to a huge variety of influences

in their own work, as well as themselves affecting

the work of others.

Japanese

colour woodcuts were a stylistic revelation to 19th

century European artists but the opening up of Japan

to the West also conversely introduced Japanese artists

to the convention of western linear perspective.

|

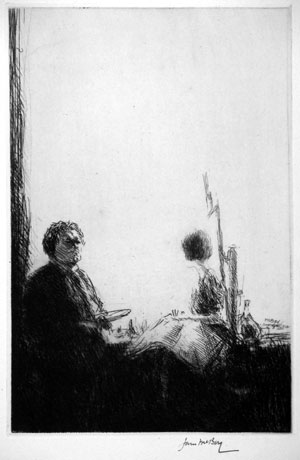

James McBey: Artist and

Model.

Etching, 1924.

A self-portrait looking

like Rembrandt. |

The reasons artists imitate and the nature of their

copying are many and various but can be summed up as appreciation, apprenticeship,

dissemination and pastiche. The catalogue contains examples

of all of these.

Emulation

is perhaps a natural adjunct of admiration. The qualities

admired in another artist’s work

can provide a creative ‘jump start’ or suggest

new directions and possibilities. Directly copying another’s

artwork can teach much about the work in question. The

physical act involving both close observation and intellectual

reconstruction gives valuable insight.

The

teenage Wierix brothers who proudly added their ages

as well as their monograms to their engraved copies of

Dürer wished to demonstrate their skill.

Before

the invention of photography, hand-engraved prints

were the only method of disseminating images to a wide

audience; and also the only way to satisfy, or commercially

exploit, a demand for iconic images.

After

the discovery of photography, the lively surface of

a hand-engraved colour aquatint was preferable to the

flat, mechanical surface of a photolithograph to reproduce

contemporary masterpieces that were housed in national

museums and unavailable to hang on private walls except

in reproduction (see above - the Villon aquatint after

Manet’s painting).

Although

too great a dependence on imitation, together with

a lack of assimilation into, or the independent development

of, the emulator’s own style, can lead to pastiches,

most artists make of their borrowing something new

and original in its own right. Compositional details

and subjects may initially be imitated but are transposed

by the unique, individually identifying touch of the

artist into something that is immediately and recognisably

his own.

A motif derived from another source can be deep

in the subconscious and unwittingly presented as an original.

As a quotation I can no longer clearly recall or attribute

perfectly expresses it, people hear the echoes but think

they are listening to the original sound.

Colour

of itself has an intrinsic resonance. Even in monochrome

prints, which are in principle simply black and white,

the black can vary from charcoal to grey-black, to

blue-black, green-black, brown-black, the ‘white’ paper

from off-white to cream, to buff, to grey-white and all

the various shades in between. The resulting effect varies

in each different combination. The more so if the monochrome

ink is a ‘real’ colour, brown, red or green

perhaps. In a full colour print there is the harmony

of the overall colour scheme, the relation of the different

colours adjacent to each other, and the magical creation

of a third colour when two colours are overprinted. Claude

Flight of the Grosvenor School wrote in his book on linocut “red

over blue over yellow gives a different result to blue

over red over yellow or yellow over blue over red, and

so forth”. Colour

of itself has an intrinsic resonance. Even in monochrome

prints, which are in principle simply black and white,

the black can vary from charcoal to grey-black, to

blue-black, green-black, brown-black, the ‘white’ paper

from off-white to cream, to buff, to grey-white and all

the various shades in between. The resulting effect varies

in each different combination. The more so if the monochrome

ink is a ‘real’ colour, brown, red or green

perhaps. In a full colour print there is the harmony

of the overall colour scheme, the relation of the different

colours adjacent to each other, and the magical creation

of a third colour when two colours are overprinted. Claude

Flight of the Grosvenor School wrote in his book on linocut “red

over blue over yellow gives a different result to blue

over red over yellow or yellow over blue over red, and

so forth”.

In

contemporary printmaking the complexity of colour printing

in the more recently invented processes of lithography

and screenprint can result in the role of the printer

being that of an important collaborator, going back full

circle to the Raphael-Raimondi relationship in the early

16th century.

However,

above all, this catalogue contains some beautiful prints,

with some interesting comparisons and juxtapositions,

and I hope you share my enthusiasm and pleasure in their

variety and find they chime sympathetic chords.

Published

summer 2009

80 pages, 183 items described, with 161 illustrations in black and white

and thirty-two in colour.

(UK

Price: £10, International orders: £15)

|

|

Artists

included in the catalogue:

- Acroyd

N

- Anderson

S

- Ardizzone

E

- Bartsch

A

- Bauer

M A J

- Bella

S della

- (Bewick)

- Blake

P

- Blake

W

- Bléry

E

- Bol

F

- Bone

M

- (Bosch)

- Brangwyn

F

- Bresslern-Roth

N von

- Brett

S

- (Bruegel)

- Brockhurst G L

- (Bronzino)

- Callot

J

- Calvert

E

- Cameron

D Y

- Castiglione

G B

- (Cézanne)

- Clarke

J

- Cornet

J P

- Craig

E G

- Crome

J

- Daumier

H

- Denne

C.

- Dietricy

C

- Drury

P

- Dufy

R

- (Dürer)

- Durig

R

- Ensor

J

- Erbslöh

A

- Fevre

F le

- Fitton

H

- Fookes

U

- Frost

T

- (Gainsborough)

- (Giorgione)

- (Goltzius)

- Gorlato

B

- Goya

F

- Griggs

F L

- Gross

A

- Haden

F S

- Hardie

M

- Hayes

G

- Hiroshige

A

- Hodgkin H

- (Hokusai)

- Holmes

K

- Hoyton

E B

- (Ingres)

- (John

A)

- (Klee)

- Komjáti

J

- Laboureur

J E

- Le

fevre F

- Leibl

W

- Leyden,

Lucas van

- Livett

U

- Kollwitz

K

- Manet

E

- Matisse

H

- McAgher(?)T

J

- McBey

J

- Meryon

C

- Michl

F

- Millet

J F

- Moncornet

B

- Monk

W

- Muyden

E van

- Nicholson

W

- Nolde

E

- Orovida

(Pissarro)

- Osborne

M

- Ostade

A van

- Palmer

S

- Patrick

J McIntosh

- Pennell

- Picasso

P

- Piper

E

- Pissarro

C

- Pissarro

O

- Platt

J

- Possoz

M

- Pott

C

- Prunaire

A A

- Raimondi

M

- Ranft

R

- (Raphael)

- Rayner

H

- Rembrandt

- Rethel

A

- (Reynolds

J)

- Ric

(?)

- Richards

F

- Robins

W P

- Rousseau

H (le Douanier)

- Salamanca

A

- Shaw

N

- Short

F

- Smart

D I

- Sparks

N

- Spencer

N

- Stephens

I

- Strang

W

- Sutherland

G

- Symons

M

- Tanner

R

- (Turner)

- Tushingham

S

- Unwin

F

- (Van Gogh)

- Velasquez

- (Vermeer)

- Villon

J

- Waterloo

A

- Watts

M

- Webb

J

- Whistler

J M

- Wilson

R A

- Wyllie

W L

- Yoshida

H

- Yoshida

T

Return to the top |