Line Engraving

Line

engraving was the first of the intaglio

techniques to be devised and was developed

in Germany and Italy about half a century

later than woodcut. Line

engraving was the first of the intaglio

techniques to be devised and was developed

in Germany and Italy about half a century

later than woodcut.

Engraving

allows a much finer line, and a concentration

of lines can give a rich subtle nuance

of tone which the woodcut cannot achieve.

The inherent light and shade in the technique

precluded added hand colouring from the

outset.

The

artist engraves directly into the sheet

of metal with a steel burin with a wooden

handle that fits into the palm of the hand,

not dissimilar to those illustrated

in the section on Wood

Engraving. The steel

is sharpened at its cutting end to a

lozenge-shaped cross-section which cuts

a V-shaped groove tailing off to a point

(a stylistic factor especially exploited

by the mannerist Haarlem School – see

the detail above and the entire engraving

by Saenredam, illustrated to the right).

The rough shaving of metal raised by the

burin at the edges of the cut line is removed

with a scraper, to give a sharp, clean, crisp

line when printed, whose slight stiffness

reflects the initial resistance of the

metal.

There

was already a long tradition of ornamental

engraving and metal chasing by the 15th

century. It is not known who first in Germany

conceived of taking impressions from engraved

designs and adapted the technique as a

process to print pictorial images from

copper onto paper, or when the earliest

intaglio printing press was made. However,

most of the earliest renowned masters of

engraving like the Master of the Year 1446,

author of the earliest dated intaglio print,

the Master of the Playing Cards and the

Master E.S. were themselves also goldsmiths.

The

invention of engraving in Italy has traditionally

been credited to the Florentine goldsmith

Maso Finiguerra, a famous niellist. Niello

was a method of decorating a small gold

or silver plaque by filling incised lines

with an alloy (nigellum) so that they read

as a black design against the brightly

polished metal. Apocryphally damp laundry

left on top of a fresh niello plate suggested

the concept of printing onto paper from

the incised plate. Impressions were printed

from niello plates and occasionally come

onto the market.

Italian

artists of the stature of Pollaiuolo and

Mantegna experimented with engraving, using

broad open parallel lines in the manner

of their ink drawings.

By

the close of the 15th century line engraving

had come of age. As in woodcut, Dürer

was the predominant figure of the period,

though Lucas van Leyden, in the Netherlands

and Marc Antonio Raimondi in Italy complete

Arthur M. Hind’s “great triumverate”.

Whereas

Dürer, Lucas van Leyden and their

followers engraved their own original designs.

Raimondi was primarily an interpretive

engraver of other artists’ drawings;

he worked in particularly close collaboration

with Raphael. As the century progressed

the reproductive tendency of engraving

increased throughout Europe, given impetus

by the founding of publishing houses such

as those of Cock, Galle, Van de Passe,

and Sadeler in the Netherlands and Salamanca

and Lafrery in Italy.

The

17th century was particularly noteworthy

for the interest in line-engraved portraiture.

France produced some exceptional masters

in Claude Mellan, Jean Morin, Robert Nanteuil.With

the principal exception of William Blake,

by the 18th and 19th centuries line engraving

had almost ceased as an original medium

(a role taken over by etching) and was

largely used to reproduce paintings. The

eloquence of line as an original graphic

expression was submerged in its conjunction

with the tone processes of mezzotint and

stipple, the better to reproduce paintings.

The introduction of steel plates in 1820,

and steel-facing for copper plates in the

mid 19th century, meant that demand for

popular images such as Frith’s “Derby

Day” could be met by thousands of

identical impressions.

Though

the subsequent invention of photographic

methods of reproduction made the commercial

engraving trade redundant later in the

century, it was not before it had subsumed

the concept of artists’ own

original printmaking in public understanding.

In

the mid-1920’s, inspired by the old

master engravings of Schongauer and Dürer,

Robert Austin revived original engraving

with its emphasis on pure line. Austin’s

example generated a small following amongst

his English contemporaries, such

as Stanley Anderson, and students

at the Royal College of Art.

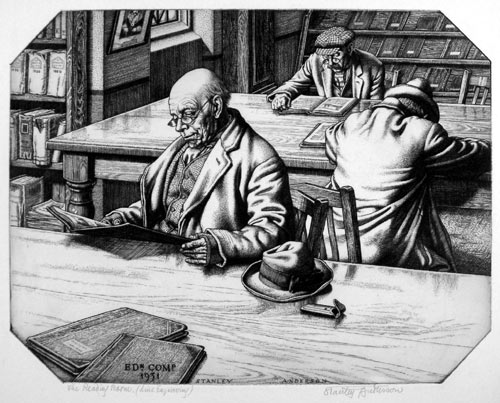

Stanley

Anderson (1884–1966): "The Reading

Room". *

Engraving, 1930. (169

x 218 mm)

In

Paris Jean Emile Laboureur had taken up

line engraving by 1916 for his cubist figure

and town scenes and in the 1930’s Stanley

William Hayter with the establishment of

his Atelier 17 in Paris took original line

engraving into abstraction and the Modernist

movement.

In

general parlance line engravings are usually

referred to simply as engravings.

(*

Stanley Anderson's "The Reading

Room",

above. This example is a fully annotated

unique impression from the cancelled plate,

the corners having been cut off and the

engraved inscription added to the plate

to show the limited edition was complete

in 1931, before the plate was sold at his

special request to an American collector.)

|