Soft-Ground

Etching

Although

the earliest soft-ground etching was made

in the 1640’s by Benedetto Castiglione,

it was an isolated example and is known

only in an unique impression. The process

was re-invented in the middle of the 18th

century in France, probably by J C François

while he was developing crayon engraving

(see here).

The

admixture of tallow to the usual etching

ground renders it soft and waxy and prevents

it from setting hard when it is applied

in a thin layer to the copper plate. The

artist draws in pencil or crayon onto paper

laid over the soft ground (see right,

for a remarkable survival of such a drawing,

by the student Robert Austin). The pressure

lifts the ground and leaves the copper

partially exposed for biting in a bath

of acid in the usual manner (i.e. as in

hard-ground etching).

The

resulting printed line has an appearance

very similar in character and grainy texture

to a pencil or crayon drawing on paper.

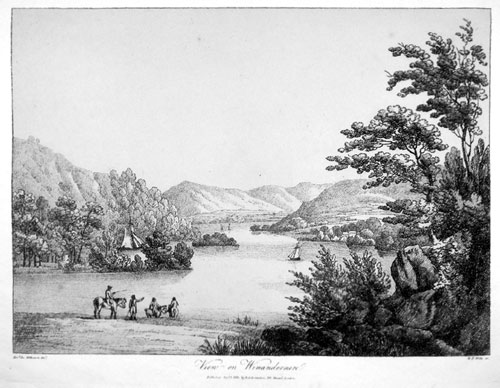

William

Frederick Wells (1762–1836): "View

on Windermere (“Winandermere”)"

Soft-ground etching, 1810, after the drawing

by Revd Jos Wilkinson.

(297 x 401 mm)

Soft-ground

etching was invented as part of the crayon

engraving process as a means of making

facimiles of drawings. In 18th century

France it remained an adjunct of crayon

engraving but in England, which had no

tradition in crayon engraving, artists

saw the advantages of its immediacy to

make original ‘multiple drawings’ by

its means. Gainsborough was an early exponent.

In the 19th century the Norwich School

artists, Crome and Cotman, and the watercolourists

David Cox and Sam Prout took it up, and

for the first couple of decades it became

a popular medium. It was largely superseded

by lithography by 1830.

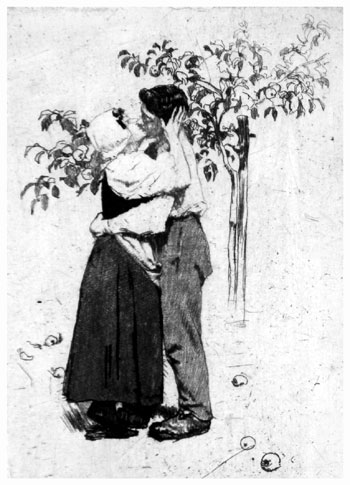

Ferdinand

Schmutzer (1870–1928): "The Kiss".

Soft- and hard-ground etching, 1904. (147

x 90 mm)

At

the end of the 19th century Frank Short

revived an interest in soft-ground etching,

though it did not attract many artists.

A similar revival of interest on mainland

Europe had a more wide-spread impact.

|