A Centenary Tribute A Centenary Tribute

to a Sculptor’s Graphic Art

The

Life and Work

of Arnold Auerbach

Auerbach

is an interesting, if little-known,

artist of the Modern British school.

He made several outstanding pieces

in the 1920’s and 30’s

which show his participation in the

dialogue with international Modernism

which preoccupied the English avant-garde in

the period between the two world wars.

Born

in Liverpool, April 2, 1898, Auerbach

was the son of a tradesman, Jonas Auerbach

and wife Eva, née Levy. Auerbach’s

grandfather, Salomon, had emigrated from

Poland.

As

a boy Auerbach attended evening classes

at the Liverpool Institute, before

taking up full-time study at the Liverpool

School of Art, where he was awarded

a pupil teachership. At Liverpool he

received the good grounding in drawing

which was the basis of all British

art college education of the period.

Drawing, he was to write later, was

the link, the common factor, between

painting and sculpture. Relief sculpture

in particular he regarded as three-dimensional

drawing. Yet the sculptor’s

draughtsmanship, like that of artists

trained as architects, is generally marked

by a distinct quality and character that

distinguishes it from a painter’s

hand.

Invalided

out of the army in 1918, having been

drafted at the age of eighteen in 1916,

Auerbach returned initially to Liverpool

where he worked with the architect

James Bramwell, carrying out the interior

designs of new buildings with both relief

sculpture and mural decoration. Through

the inter-War years sculpture was to

be Auerbach’s main pre-occupation.

He

first exhibited in 1919, at the Maddox

Street Gallery in Liverpool and from

1921 he contributed to the annual Autumn ‘salons’ at

the city’s Walker Art Gallery.

In 1921 Auerbach moved to London where

he shared a studio with the painter Robert

Arthur Wilson, and exhibited work at

the noted Chenil Gallery. Later in the

same year he made his first visit to

the Continent, travelling through France

and Austria en route to Switzerland.

In Paris he was particularly impressed

by the contemporary sculpture of Maillol,

Archipenko, Laurens, Lipchitz and Zadkine,

though it was a few years before this

interest was reflected in his work.

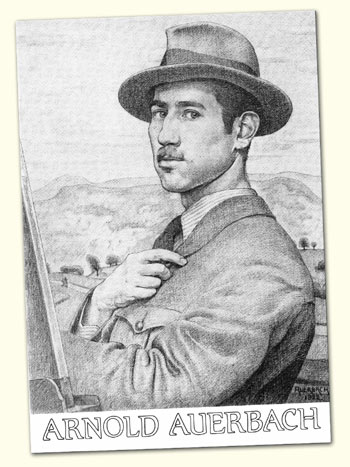

He

celebrated his return to London and

artistic ‘coming of age’ in

a fine finished pencil self-portrait

(illustrated on the front cover) very

much in the tradition of the late Italian

Quattrocento, recalling portraits by

Piero della Francesca and Giovanni Bellini.

Northern European old master painters

such as Dürer and Rembrandt had

similarly portrayed themselves as a record

of different stages of their careers.

Auerbach’s Self-Portrait at

the age of twenty-four is the summation

of his student days; an avowal of his

powers as a draughtsman and an anticipation

of the art world opening before him.

He took a studio in Adelaide Road in

Hampstead and within a couple of years

showed for the first time at the Royal

Academy, in 1923.

Through

the 1920’s

Auerbach was commissioned as an architectural

sculptor to decorate the interiors

of several Art-Deco buildings. Little

of this work survives, for instance

The News Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue,

which he ornamented with a relief tryptich

of standing female nudes with pleated

drapes, was destroyed in World War

II, though he kept the original plasters

in his studio till his death, and made

a related etching. A major commission

in 1927 was for the reliefs for the palace

of the Nawab of Rampur in India.

By

the mid-1920’s Auerbach’s

sculpture and drawings reflected an awareness

of Ancient Egyptian stance, simplification

and monumentality of form. In the later

20’s and the early 1930’s

he experimented with the broken planes,

angularity and semi-abstract patterning

of cubism.

During the Second World War Auerbach

took up his first teaching post, at Beckenham

Art School, replacing Henry Carr who

had been appointed a War Artist. After

the War he was invited to join the staff

of the Regent Street Polytechnic, first

in the School of Architecture, later

in the School of Art where he taught

still life and portrait painting. Subsequently

he was at Chelsea School of Art, until

his retirement in 1964. Afterwards he

continued to teach at the Stanhope Institute

until 1968.

Ill

health had forced Auerbach to give

up making sculpture in the mid-1950’s

and concentrate on the less physically

demanding medium of painting.

After

World War II Auerbach had, in common

with many artists, returned to naturalism.

A series of etchings from 1949 is obviously

made directly from the model in lifeclass.

Several models recur in various plates

in different or repeated poses. Teaching

in art schools gave easy daily access

to life classes.

In his book Sculpture,

a History in Brief, written

in 1952, Auerbach discusses abstraction

and realism in general but thereby

gives an insight into his own attitudes

and approach.

If

the artist chooses abstract forms to

take the impress of his feelings it

is because, in so far as the forms

become more generalised, so much the

less will they tend to resemble particular

things in the natural world. The less

therefore they will be likely to convey

precise intellectual information, and

will the better respond to shades of

pure feeling… But

we are entitled, also, to ask whether

these abstract shapes are really capable

of carrying such a weight and variety

of meaning, or responding with sufficient

flexibility to … complex feelings.

Moreover, so enormous is the variety

of forms in nature, and so consistently

in front of our eyes, that it is almost

difficult to avoid making a shape which

is not in some degree reminiscent or

suggestive of living forms…

Yet

in reality, and in spite of the existence

of a natural tendency towards either

realism or abstraction, with extremes

at either end, the supposed opposition

of abstract or geometric shapes and

naturalistic ones is based on a misunderstanding

of the fundamental nature of art. Whether…made

in the likeness of anything else outside

itself or not, that descriptive likeness

is never its essential…quality.

The quality which is its irreducible

quality resides in its own physical shape

and the feelings which may be aroused

by the sort of order that shapes establishes.

For that order, that physical relationship

of the masses, the planes, the lines – its

form – is the representative spirit

of its maker.

This

sketch has been written with hardly

any direct mention of ‘beauty’,

the one quality which it has always been

the special business of art to produce.

For beauty comes perhaps better veiled.

The beauty of sculpture resides not in

what it records, though it may well record

beauty too, but in some fine shaping

of the material, so that the spirit enters

into its form. Where there is sculptural

form there is beauty, for the mark of

life is on it.

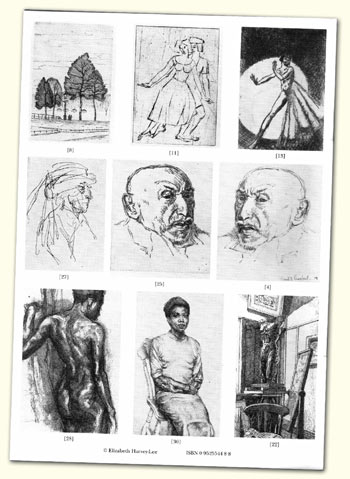

The Etchings The Etchings

Auerbach

took up etching in the early 1920’s

during the Etching ‘Boom’ and

produced plates intermittently through

the 20’s and early 1930’s.

The images are sometimes entirely original

though more frequently related to his

contemporary drawings, paintings or sculpture.

They include London and Liverpool street

scenes, and studies of heads and figures.

The earliest plates are tonal and more

often in drypoint, which he could work

directly into the plate without ground

or need for acid. After 1926 there is

a greater emphasis on line and the drawing

is more schematic. Animals and female

nudes take the stage.

From

1928/9 to about 1934/35 Auerbach produced

several interesting cubistic designs,

quite outside the canons of traditional

Modern British etching. In general,

period impressions from these plates

are no longer available. In 1987 I

printed editions of 2 to 5 proofs only

from nine plates before selling the

plates. Specially for this centenary

exhibition Jeff Clarke ARE has kindly

printed small editions from two further

plates, and reprinted the two plates

from which only 2 proofs had been taken

in 1987.

After

1935 there is a hiatus of more than

a decade in Auerbach’s

etching output, during which he would

seem to have reassessed his relationship

to Modernism.

Ironically,

when he resumed etching after the War,

in the late 1940’s,

the market for black and white etchings

had collapsed, yet the following decade

saw his greatest activity in the medium.

At a period when ill health forced him

to abandon the greater physical rigours

of large scale sculpture, etching allowed

him to continue to explore the form of

the human figure now denied to him in

sculpture. His later paintings, by contrast,

were predominantly studio still lives.

The latest dated etching of which I am

aware is from 1960.

The

later plates are numerous and were

either drawn directly from the model

or are based on Auerbach’s

drawings, paintings and even sculpture,

sometimes from earlier decades. The

human figure predominates. The later

plates are more typically etched, rather

than the drypoint of the pre-War plates,

Often he used a double pointed stylus

which gives the effect of a broad freely-drawn

line searching out the form in a coming

to terms with a two-dimensional expression

of shapes he felt in the round.

Auerbach probably never owned his own

press but either used commercial plate

printers or the facilities of the art

colleges where he taught. Several of

the impressions left in his studio were

pattern proofs for the printer.

Auerbach

married late, only in 1954, to a charming

Scots lady, Jean Campbell, whom he

had first met towards the end of the

War. Jean was also a professional artist,

trained at the Glasgow School of Art,

who worked for many years as an artist

with the Admiralty. Now aged ninety-two

(in 1998) it is due to her generosity

that this exhibition is possible, as

the previous posthumous exhibition

of Auerbach’s sculpture. Arnold’s

sculpture was celebrated in an elegant

catalogue by René Reichard of

the Galerie Huber und Reichard in Offenbach

am Main. This brief tribute to Arnold

Auerbach as a graphic artist is dedicated

to Jean.

A5

(210 x 148.5 mm) ; 32 pages, with 34

illustrations of which 3 are in colour.

An exhibition catalogue of 41 items,

and a checklist of 142 etching plates,

all that remained in the artist’s

studio on his death.

(UK

price: £5, International orders: £8)

|