Lithography

The

beginnings of Lithography – ‘Polyautographs’

(Pen

Lithographs)

The

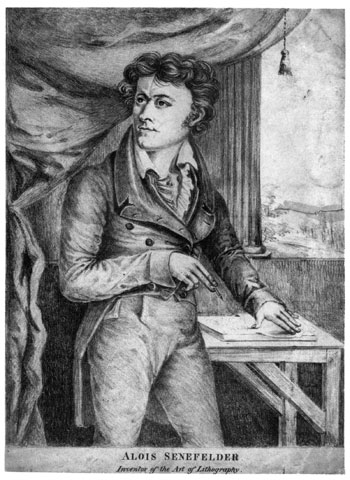

Munich actor and playright, Alois Senefelder

(1771-1834) was seeking an economical method

of duplicating plays and sheet music when

he discovered lithography (from the Greek lithos and

graphos, 'stone

writing'), a method of ‘Chemical

Printing’,

in 1798. His system was based on exploiting

the simple chemical fact of the mutual

repellence of grease and water. Senefelder

(see illustration below) quickly

appreciated that the technique would be

equally ideal for creating artists’ printed

drawings.

While

briefly in partnership with the music publisher

Johann Anton André, Senefelder visited

London to acquire the English patent, though

he sold out to André and it was

André’s son, Philipp André,

who became the patentee.

|

Alois

Senefelder, working on a lithographic

stone. An anonymous early

19th century

crayon lithograph. |

|

André was

especially interested in the technique

as a new graphic art and sent the necessary

materials to artists inviting them to experiment.

In 1803 he published in London the first

ever artists’ original

lithographs, under the title SPECIMENS

OF POLYAUTOGRAPHY. The initial twelve

contributing artists included Benjamin

West, the president of the Royal Academy,

Henry Fuseli, James Barry and Thomas Barker

(see above right).

These

rare English incunabula of lithography

were all drawn with the pen. The artist

drew on a porous limestone block with pen

and greasy lithographic ink, known later

as tusche, composed of wax, soap and lampblack.

When the treated stone was inked up for

printing the ink adhered only to the areas

of the original greasy drawing and the

resulting impression bore a remarkable

resemblance to an original pen drawing.

After

1810, later artists have only rarely used

the pen for lithography. Their productions

are usually termed ‘pen lithographs’ to

distinguish them from the more usual crayon

lithography, 'polyautograph' being reserved

for the very early examples.

Crayon

Lithography

It

was on his London visit in 1800 that Senefelder

perfected the chalk (or crayon) manner of

lithography, which has subsequently had

the largest following amongst artists.

In crayon lithography, the artist draws

with a greasy lithographic crayon and the

resulting printed impressions have the

character of chalk drawings. Depending

on the pressure and thickness of his line

in drawing with the crayon the artist can

achieve a range of tones from silvery grey

to intense black. ‘White’ areas

are either undrawn or created with the

scraper (see right, the illustration

of Gavarni’s self-portrait in his studio). Where the greasy drawing is scraped

away the ink will not adhere in the printing. For

greater range of tone artists sometimes

work with crayon and tusche together.

Lithotint

Another

variation, also first adopted by Senefelder

for ‘tinted’ lithography and

later called lithotint was adapted by Whistler

to a tonal monochrome technique. In lithotint

the artist draws with brush and tusche

washes variously diluted with water according

to the desired tonal effect (see to

the right, below, Lunois’ brush lithograph

of “La Guitariste”). Lithography

is unique in this versatility of being

both a linear and a tonal technique.

Lithographic Process and Printing

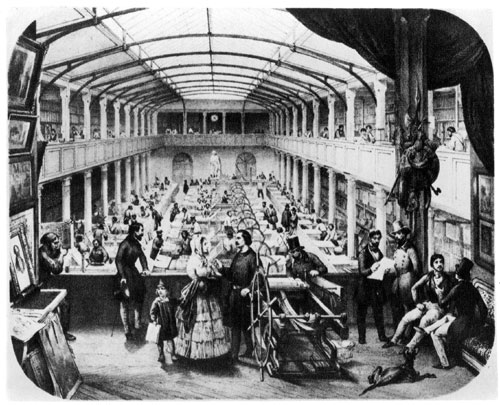

"Imprimerie

Lemercier, rue de Seine, Paris". Lithograph,

c1845

One of the leading lithographic printing

firms in 19th century France.

Senefelder

also invented the lithographic press for

printing lithographs (see illustration

right).

Preparing lithographic stones for printing

is a complex and laborious process, which

is generally carried out by a professional

lithographic printer working in close collaboration

with the artist. The lithographic matrix

traditionally was limestone, from the Solenhofen

district in Bavaria, near Munich, which

was particularly porous and had an affinity

for grease. The lithographic crayon allows

the artist to draw freely and readily on

the stone (see right). The greasy drawing

material seeps into the pores of the stone.

The stone is painted with gum-etch (gum arabic

dissolved in water with nitric acid) to

increase the porosity of the undrawn areas

so they hold water when dampened with a

sponge, whereas it is rejected by those

areas which have absorbed the greasy drawing.

Conversely, these areas accept the ink

when it is rolled over while it is repelled

by the damp areas. Paper is laid over the

stone and the image is transferred as the

stone is moved laterally through the press

beneath a scraper or roller.

The development and spread of Lithography

After

the initial period of experimentation lithography

was slow to be taken up by artists in England

(an early exception is James Ward). From

the 1830’s it increasingly superseded

aquatint for topography and decorative

prints but it was not till the 1890’s

that British artists once more took it

up as an original expression, which was

fostered and promoted by the founding of

the Senefelder Club in 1908.

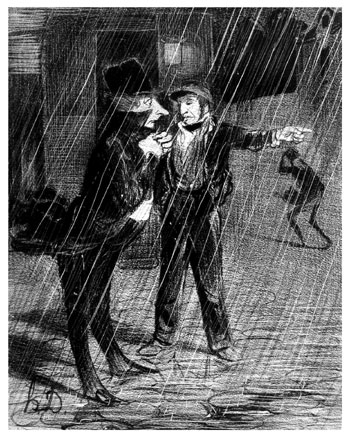

Honoré Daumier

(1808–1879): "Comment à Chaillot!…"

Lithograph

1839. (240 x 189 mm)

An

unhappy customer on a dark rainy night

has taken the last ‘bus’

in

the wrong direction and it being midnight

the service is finished.

Daumier

has scratched into the surface of the

stone to create the

‘white’ lines

of the rain.

French

artists were more receptive to the new

technique. The rich blacks, the tonal

subtleties and the spontaneity of drawing

particularly appealed to the great Romantic

artists such as Géricault and Delacroix.

Goya, in exile in Bordeaux at the end of

his life took up lithography in 1825 at

the age of seventy-nine. Books and political

periodicals exploited lithography for original

illustrations and caricatures (see

Daumier immediately above, and Gavarni, above

right).

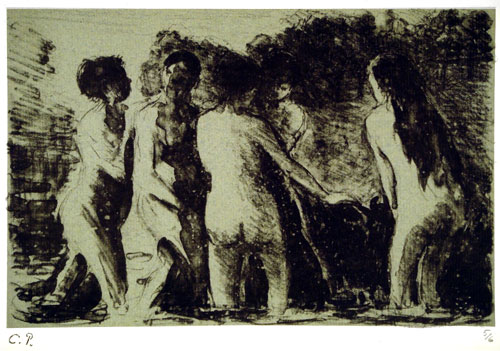

Camille

Pissarro (1830–1903): "Théorie

de Baigneuses".

Lithograph, c1894–97. (130

x 200 mm)

(This

example from the posthumous edition of

six, printed on blue-green

paper. Stamped

with the artist’s initials and numbered

in pencil.)

From

the 1850’s there is a hiatus, followed

by a flowering throughout Europe in the

1890’s, of lithography for artists’ original

prints, particularly as a colour technique.

The technique has continued to be popular

with modern artists such as Matisse (see

right) and Picasso.

Transfer Lithography

|

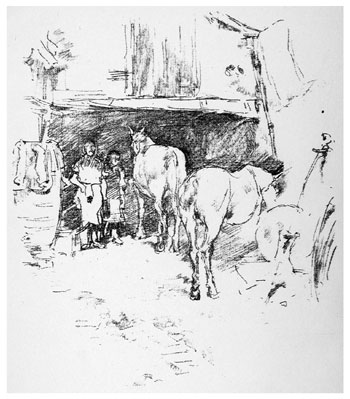

James

McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

"The Smith’s Yard, Lyme Regis".

Transfer lithograph, 1895

Issued in ‘The Studio’ 1897. (200 x 140 mm) |

|

Lithographic

stones being unwieldy to handle and nigh

on impossible to take outside to work directly

on a motif from nature, artists sometimes

made use of lithographic transfer paper

on which to make their lithographic drawings.

Senefelder had also instigated this method

at the inception of lithography.

Lithographic

transfer paper has the advantage that the

image is reversed in being transferred

to the stone so that the print reads in

the same direction as the original drawing;

however the impressions are generally more

delicate and with less tonal contrast than

is possible when the artists draws directly

onto the stone. Compare the Whistler and

Daumier lithographs above: Daumier

drew onto the stone; Whistler used transfer

paper.

Transfer

lithographs were the cause of a celebrated

law suit in 1897 between Sickert and Joseph

Pennell. Sickert’s

assertion that Pennell’s prints were

not original lithographs because they were

drawn on transfer paper, was thrown out

of court. |