Cliché-verre

Impact

of the Discovery of Photography

The

development of photography in 1839 by Fox

Talbot in England and Daguerre in France

had considerable impact on traditional

printmaking. Artistically, as in painting,

it suggested new compositional devices

and viewpoints, and gave insight into the

two-dimensional representation of movement.

Technically it made reproductive engraving

redundant and focussed traditional printmaking

techniques entirely on original artistic

expression.

Long

before photography was adapted to the reproductive

processes of photogravure and collotype

(photolithography), the light-sensitive

properties of photographic paper suggested

exciting new possibilities in artists’ original

printmaking, methods involving no camera,

but where the artist himself hand-drew

and printed an original photograph, what

has been evocatively called “etching

with light”.

Photogenic

Drawing

Fox

Talbot first described the basic principle

of photography, in a paper to the Royal

Institute in 1839, as "photogenic

drawing"

(see right and below).

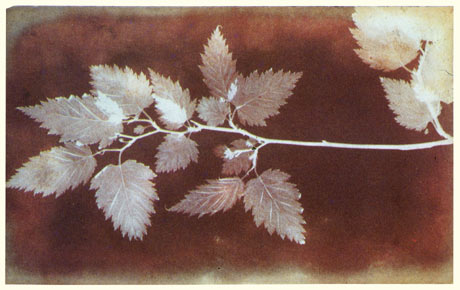

William

Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877): “Leaves”.

‘Photogenic drawing’ c1838.

He

placed an opaque object (a fern leaf) on

light sensitive paper (paper impregnated

with silver chloride) and exposed it to

sunlight. The light turned the paper black

except where it was covered by the fern.

The ‘white’ negative image

of the fern was fixed by immersing the

sheet in a solution of alkaline bromide

and chloride.

English prints from glass, etched

with light

It

was a logical extension to reverse the

scheme and only allow the sun to penetrate

positively through a linear design hand-drawn

by an artist into an opaque ground.

Talbot himself recognised this as early as 1834 and organised a few experiments while he was in Bellagio; though having no artistic pretensions he asked others to draw on his glass plates.

By

1839 the process was attracting wider interest and William Havell, his brother Frederick

and fellow landscape artist, James Tibbits

Willmore, exhibited photographic drawings

at the Royal Institute that year. They covered a

glass plate with etching ground and drew

into it. Laid against light-sensitive paper

in sunshine, the sun exactly transferred

the artist’s drawing from the glass

to the paper. Sadly, with the exception of an earlier ‘Talbot’ experiment, no impressions of these

"photographic drawings", English

anticipations of the French clichés-verre, have

survived. A record does remain of a charming

cliché-verre drawn on coated glass,

by the caricaturist George Cruikshank, in

1851. It is a ‘Pickwickian’ portrait

of Peter Wickens Fry (died 1860), an early

amateur photographer and founder member of

the London Photographic Club, who is shown

looking through a lorgnette at a piece of

paper, obviously a cliché-verre print,

with above him the caption “Etched

on glass. Dear me! how very curious!”.

French

cliché-verre

In

1853 independently in France similar experiments

were made by the amateur landscape photographer,

Adalbert Cuvelier, and christened cliché-verre "glass

prints". A French refinement was to paint

the design in either oil paint or printing

ink on the glass and dust it with powdered

white lead or collodian. The varying densities

of the ‘emulsion’ controlled

the amount of sunlight that could filter

through to ‘colour’ the light

sensitive paper, so that the artist

could print in tones from pale grey through

to black. A thick white collodian emulsion

of uniform density could also be used as

a ground into which a purely linear motif

was drawn.

Cliché-verre

is almost exclusively associated with Corot

(see right) and the Barbizon landscape

painters, and largely confined to the 1850’s

and 1860’s.

Théodore

Rousseau (1812-1867): “The Cherry

Tree at La Plante-à-Biau”.

Cliché-verre,

c1862. (217 x 275 mm)

Barbizon

on the outskirts of the Forest of Fontainbleau

had already attracted regular visits from

landscape painters wishing to paint in

the open air (plein-air) directly

from nature. The 1848 Revolution in Paris

determined the permanent migration of J F

Millet and Charles Jacque. Constant Dutilleux

and Daubigny were regular guests at the village

inn (as were Georges Sand, the Goncourts

and other romantics). Adalbert Cuvelier

visited annually bringing his photography

students from Arras. In 1859 his son Eugène

married the inn-keeper’s daughter

and settled in Barbizon. Eugène

Cuvelier showed the cliché-verre

process to Millet, Rousseau (see illustration

above) and Daubigny (see illustration

above right) and printed their

glass plates, which remained in his possession.

Few early impressions (printed on thin salted

or albumin paper) have survived.

The

Cuvelier collection of cliché-verres

was re-printed in small editions of 10-15

prints in 1911 when it was acquired by

Bouasse-Lebel. The plates passed to Le

Garrec, successor to Edmund Sagot at the

Galerie Sagot-Le Garrec, who printed the

principle edition (150) before chipping

the corners of the glass plates as cancellation

and giving them to museum collections.

The Le Garrec impressions are on gelatine

paper and retain the photographically printed

scratches and fingerprints in the borders

and the ‘black’ edge of the

glass plate. |