Aquatint

The

Technique

The

preoccupation central to later 18th century

French printmaking of reproducing artists’ drawings

in facsimile also led to the invention

of aquatint as a means of achieving areas

of continuous tone in an etching similar

to the washes in an ink or watercolour

drawing. Until the 20th century aquatint

was nearly always used in conjunction with

the etched line.

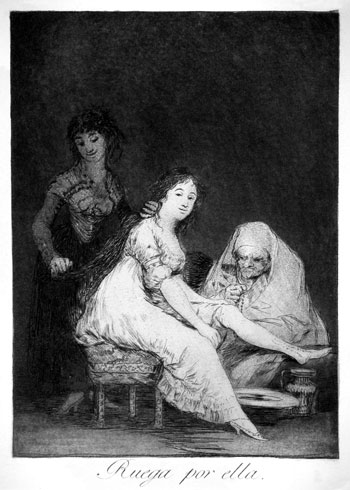

Francisco

Goya (1746–1828):

"Ruega por ella"

(She prays for her). Etching and aquatint,

1799.

Plate 31 of the ‘Caprichos’. (205

x 151 mm)

The

principle method involves dusting a layer

of powdered resin onto the copper plate.

This can be done by hand but the plate

is more usually placed in a dust box. Bellows

raise a cloud of resin dust in the box

which is then allowed to settle as an even

layer over the plate. The resin is fused

in place by the application of gentle heat

from below. The artist stops out by painting

with acid-resist varnish those areas of

the plate which do not require tone. When

the plate is immersed in acid, the acid

can only bite around and in between the

exposed fused particles of resin, which

results in a fine network of lines, like

miniature crazy paving (see enlarged

detail of Manet, below right). The

size of the individual particles of resin

dust, whether coarse or very fine, determines

the grain of the aquatint. The length of

immersion in the acid controls the depth

of biting and hence the ‘depth’ (intensity)

of the resulting printed tone.

Two

other methods can be used to achieve an

aquatint ground, the spirit ground and

sugar-lift aquatint.

Spirit

Ground

In

spirit ground the powdered resin is dissolved

in alcohol and poured over the plate. The

alcohol evaporates and leaves the very

finely granulated resin on the plate, to

be treated as before. This method achieves

the finest grain of aquatint.

Sugar

Lift Aquatint

In

sugar-lift aquatint the artist draws his

design directly onto the untreated surface

of the copper plate with a brush and a

solution of india ink and sugar. The plate

is then covered with acid-resisting stopping-out

varnish. When set, the plate is placed

in warm water. The pure varnish ground

holds firm except where it covers the sugar-lift

drawing. The sugar solution slowly dissolves

in the water lifting the ground to expose

the copper. The exposed areas are then

dusted with resin and bitten in the usual

method of aquatint. Sugar-lift makes possible

a linear as well as a tonal treatment of

the plate in pure aquatint without the

usual adjunct of etched lines. As the bitten

image is created directly from the artist’s

brushstrokes on the plate it is a most

painterly technique (see enlarged

detail of Picasso).

History

of Aquatint

Jean

Baptiste Le Prince claimed the discovery

of gravure au lavis (literally “etching

with wash”), though in fact Jan van

de Velde IV in the 17th century had, untrumpetted,

anticipated him in isolated examples of

aquatint, and Le Prince’s contemporary

St Non was an equally early practitioner

of the technique. The tonal quality of

aquatint was also anticipated in the 17th & 18th

centuries by etchers such as Rembrandt

and Mulinari in their use of a sulphur

tint. Powdered sulphur, dusted over the

plate already thinly spread with oil, corroded

the surface so that it held ink as a uniform

tone in printing. Burnishing gave tonal

variations.

Le

Prince described the process of aquatint

for the first time in a paper to the French

Academy in 1768. Le Prince’s aquatints

were printed in sepia ink in imitation

of his sepia wash drawings which they sort

to emulate. In France the technique was

soon adapted to coloured inks printed from

multiple plates made by professional engravers

after paintings by the leading artists

of the day (see page on Colour

Intaglio).

Goya

(see above) was one of the few great artists

in the late 18th century to recognise the

potential of the medium for original printmaking.

The

term 'aquatint' was coined in 1776, by

Paul Sandby, to describe his invention

the previous year both of the spirit ground

technique and the sugar-lift method. (Today

the single word ‘aquatint’ suffices

for all the versions of the technique.)

English watercolour artists found the process

congenial both for creating original prints

(Sandby - see illustration, top right,

Thomas Malton, William Daniel &c.)

and for the reproduction of their topographical

and sporting watercolours by professional

aquatinters such as Stadler, Bluck, Sutherland,

Hill etc. who either etched the whole plate

or merely added aquatint tone to a plate

etched in line by the artist. The Swiss

also produced particularly fine reproductive

topographical aquatints at this period

when early tourists began to appreciate

the picturesque qualities of the Swiss

landscape. The reproductive aquatints of

the first half of the 19th century were

usually hand-coloured in the publisher’s

workshop to a model supplied by the originating

artist. Largely for economic reasons this

sort of aquatint was superseded by lithography

from about 1840.

Aquatint

enjoyed a limited revival from 1890–1940

as an artist’s technique. Picasso

particularly enjoyed using the sugar-lift

process (see illustration). |