Drypoint

In

etching if the artist draws vigorously

into the ground he may unintentionally

score into the copper beneath. The origins

of drypoint probably lie in such an accident.

Though closely allied to and often used

in conjunction with etching, pure drypoint,

as its name implies, involves no use of

wet acid. The artist works directly into

the copper surface with a drypoint needle

or a burin. In scoring the copper the needle

raises a shaving of metal on either side

of the furrow, which holds the ink and

prints as a rich velvety smudge known as

the “burr”. In engraving this

is polished away to give a sharp clean-cut

line but the residual burr is the chief

characteristic and beauty of drypoint. In

etching if the artist draws vigorously

into the ground he may unintentionally

score into the copper beneath. The origins

of drypoint probably lie in such an accident.

Though closely allied to and often used

in conjunction with etching, pure drypoint,

as its name implies, involves no use of

wet acid. The artist works directly into

the copper surface with a drypoint needle

or a burin. In scoring the copper the needle

raises a shaving of metal on either side

of the furrow, which holds the ink and

prints as a rich velvety smudge known as

the “burr”. In engraving this

is polished away to give a sharp clean-cut

line but the residual burr is the chief

characteristic and beauty of drypoint.

Repeated

printing wears the burr away so that only

a few (from twenty to forty) good drypoint

impressions can be taken before the plate

becomes tired. Steel facing, introduced

in the etching boom when larger editions

were in demand, increased a plate’s

potential to a hundred or so impressions

without signs of deterioration. Proofs

prior to steel facing are always richer.

Steel

facing has also been used to

prolong artificially some of the plates of

the Impressionist artists such as Renoir

and Berthe Morisot, which are still being

printed today, though all traces of burr

have long since disappeared and the impressions

print as ghosts by comparison with earlier

impressions.

Depending

on the amount of burr raised drypoint is

used to create either strong furry lines,

or in crosshatching a dark almost continuous

tone, or a delicate silvery tone from the

lines placed close together.

REMBRANDT Harmensz. van Rijn (1606-1669)

“The Triumph of Mordecai”.

Etching and drypoint, c1641. (178 x 218 mm)

A

few isolated examples of drypoint are found

in the early Northern masters but Rembrandt

was the first to develop the technique

to any extent and from the 1640’s

he used it increasingly on his plates in

conjunction with the etched line.

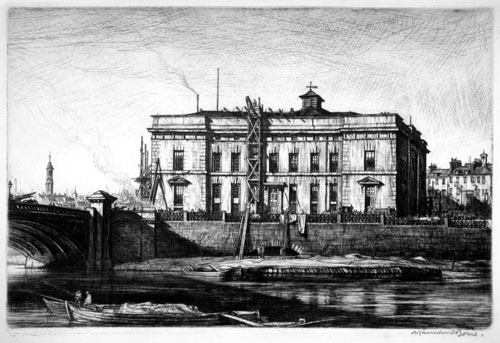

Muirhead

Bone (1876–1953): The Old Justiciary

Court-House, Glasgow.

Drypoint,

1911. (133 x 199 mm)

It

was only at the end of the 19th century

and in the early decades of the 20th century

that drypoint was exploited in its purest

form. British artists, inspired initially

by the example of Rembrandt, found the

technique particularly sympathetic. Some,

like Muirhead Bone (compared in his day

to Rembrandt), Francis Dodd and Henry Rushbury

devoted their printmaking to it almost

exclusively. French artists of the Belle

Epoque and the German Expressionists also

found it a powerful medium of expression. |