Etching

Etching

allows spontaneity and informality in drawing

on the plate and consequently it is the

technique most closely associated with

artists’ original printmaking; and

that with the longest continuous history.

Developed

originally as a means of armourers’ decoration,

etching was adapted as a pictorial printing

technique in the early years of the 16th

century. Perhaps because of this early

association with armour, the first German

exponents, Dürer, Hirschvogel, Lautensack,

Amman and the Hopfers used iron plates,

which gave a coarser, more uneven line,

than the now traditional copper. Lucas

Van Leyden in the Netherlands and Parmigiano,

the first etcher of note in Italy, however

employed copper for their plates. Copper

prevails to this day, though in the 20th

century zinc has also been used as a cheaper

alternative, especially for very large

plates, by artists such as Frank Brangwyn.

The

word ‘etching’ has its roots

in the old High German ezzen “to

eat”, for traditionally the drawing

is eaten (‘bitten’ in modern

parlance) into the copper plate by acid.

The etching acid is known as the ‘mordant’ (from

the French mordre “to bite”).

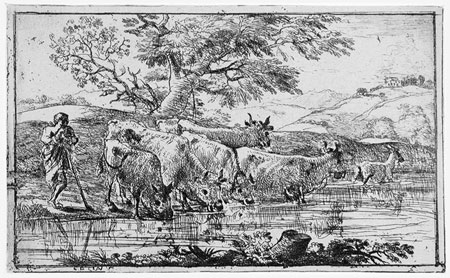

Claude

Gelee (known as ‘Claude’ or

Claude Lorrain) (1600-1682):

“The

Herd at the Watering Place”. Etching,

c1635-60. (107 x 174 mm)

The

artist lays a dark ground onto the copper

plate, covering and sealing its surface.

A ball of solid ground, composed of mixed

waxes, resins and gums, is applied to the

heated plate so that it melts and spreads

easily. In previous centuries the ground

did not come ready coloured, but was darkened

by holding the prepared plate over a lighted

taper (see right) whose smoke was absorbed

by the ground and turned it black. The

ground sets hard as soon as the plate is

cold. The dark colour enables the artist

to see the marks of the etching needle

as he draws through the ground and exposes

the copper beneath.

When

immersed in nitric acid (or hydrochloric

acid mixed with chlorate of potash – the

Dutch bath) the exposed copper reacts with

the acid which chemically cuts the drawing

into the plate. In earlier times the plate

was bitten by building low wax walls around

the perimeter and pouring the acid over;

today it is placed in a small ‘bath’ of

acid. The longer the plate is exposed to

the acid the deeper will the lines be etched,

the more ink they will hold and the heavier

and thicker will be the resulting printed

line. Variety of tone, almost amounting

to colour, can be achieved by controlling

the degree of etching of different areas

of the plate.

Stop-out

varnish is applied to lightly bitten areas

to protect them if the plate is further

immersed to strengthen bolder areas of the

design.

‘Trial

proofs’ may be printed at different

stages of the plate’s progress so

the artist can see how his print is developing. ‘Counterproofs’ (see

below right),

which reverse the image, are sometimes

printed by passing a freshly printed impression

back through the press to print on to a

new sheet of paper. The counterproof is

in the same direction as the work on the

plate and the artist can experiment with

amendments by drawing or painting on top

of the counterproof as a guide to how he

should proceed on the plate. Artists also

sometimes make these sort of amendments

to trial proof impressions, which are known

as ‘touched proofs’.

Rembrandt

Harmensz. van Rijn (1606-1669)

“The Turbaned Soldier on Horseback”

Etching, c1632. (83 x 58 mm)

Only

isolated experiments with etching were

made in the 16th century but the following

century it flowered as artists became aware

of the expressive possibilities of its

flowing eloquent line. The 17th century

was indeed a golden age of etching. Many

of the greatest painters of the period,

and particularly the generation active

1625-45, were enthusiastic etchers; Rembrandt

and Ostade in Holland; Reni and Castiglione

as well as the Spanish Ribera and French

Claude in Italy. For Jacques Callot, Stefano

della Bella, Abraham Bosse and Wenceslaus

Hollar it was their principle form of expression.

Giovanni

Battista Tiepolo (1697–1770): "An

Astrologer with a young Soldier".

Etching, c1740. (one of the ‘Vari Capricci’ series). (134

x 170 mm)

In

the 18th century in England, France, and

Holland printmaking became largely concerned

with reproduction, utilising other printmaking

techniques, but in Italy Canaletto, Tiepolo

and Piranesi continued the tradition of

original etching.

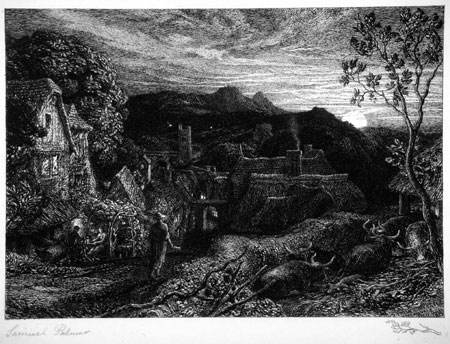

Samuel

Palmer (1805–1881): "The Bellman". Etching,

1879.

A ‘remarque’ proof – see

the small branch etched into the lower

border of the plate. (190 x 251 mm)

The ‘Etching

Revival’ in the 19th century was

initiated in Britain by the artists of

the Norwich School and in France by Daubigny

and the artists of the Lyon and Barbizon

schools, all of whom were inspired to follow

the example of the great Dutch masters

of the 17th century. The founding of etching

clubs and the societies of Painter-Etchers

gave a broader base of popularity and by

the end of the century etching was once

again practised widely as an original expression

by artists.

Charles

Meryon (1821-1868): “L’Abside

de Notre Dame”. Etching, 1854

(one of Meryon’s series of ‘Eaux-fortes

sur Paris’). (163 x 298 mm)

Paris,

as the artistic centre of Europe, had a

seminal influence in exposing artists from

all over Europe and America to original

printmaking. The

various art journals illustrated with original

impressions of etchings further promoted

the technique internationally.

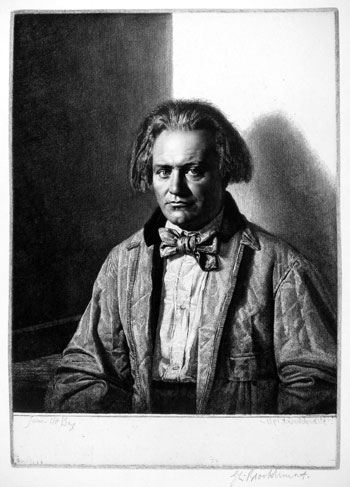

Gerald

Lesley Brockhurst (1890–1978):

"Portrait of James McBey".

Etching, 1931. (267 x 190 mm)

Brockhurst was a superb technician

and none of his peers could

do such fine needling

or create such density of tone and texture.

By

the early decades of the 20th century there

was an ‘Etching

Boom’ in England and a thriving international

market supported by the Print Collectors’ Clubs

which only collapsed with the Depression.

Etching

lends itself to two stylistic approaches

which can be recognized throughout its

history, the calligraphic open linear style,

combined with expressive ‘blank’ areas

of paper and the tonal method of cross

hatching with sometimes scarcely a glimmer

of paper showing through the closely worked

mesh of lines. Compare the etchings

above by Claude, Rembrandt and Boreel

with the Palmer and Brockhurst.

Artists

also frequently mixed etching with other

intaglio techniques, engraving, drypoint or aquatint. |